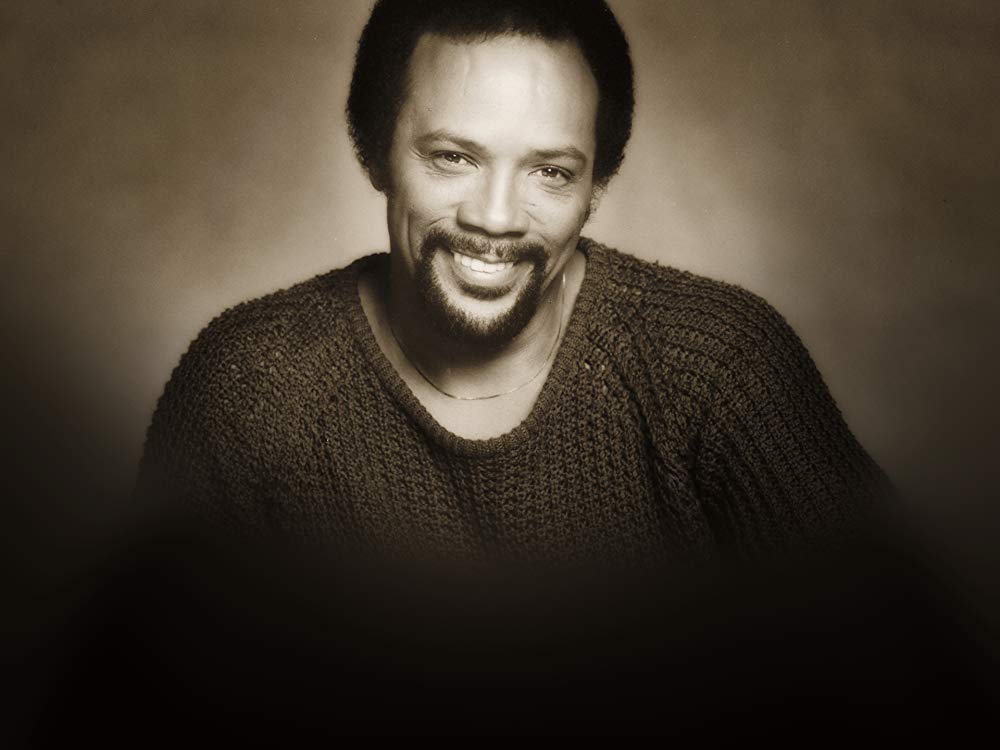

Quincy Jones

Quincy Jones

Introduction

Blackness. From Lead Belly to Miles Davis, from John Coltrane to Bootsy Collins, the vast history of black music in America is more at our CD-skipping finger tips than ever before. The sound of blackness – from the most primitive blues to the wildest free jazz – is available in pure and unadulterated form. This is in marked contrast to how black music in the States first started, when black music was isolated, segregated and ghettoized. But while we can now savour this incredible range of styles on CDs, our access to blackness on the movie soundtrack is not so easy. And the recouping of a black sensibility in the cinema has been and remains far more difficult.

Historically, cinema is a hybrid created by cross-fertilizing the music publishing industry with motion picture technologies. In fact, the Tin Pan Alley era of song publishing predates the cinema. Prior to cinema and recorded music, pop ditties were peformed and sung by the consumers themselves when they bought sheet music and took it home. There was no clear sense as to what image should accompany a song, nor was the performer or singer a purchasable commodity. Once movies became popular throughout both the silent and sound eras, movies were deemed an ideal promotion vehicle for songs. This resulted in songs being visualised in terms of scenarios and performers. And while many of the Tin Pan Alley era of songs were in the black vernacular of jazz and blues, there was no holistic space for African Americans to perform their music in the cinema. Things could sound black, but they had to look white.

This resulted in a visual homogeneity, thickened by successive layers of conventions, icons and clichés. Racial, ethnic and regional differences which musically could thrive as characteristic stylings were either rendered absurd or harshly suppressed when film images came into play. Where the sound of blackness enjoyed a pervasive presence as music alone, it consequently paled on the white screen – and would continue to do so for many decades to come. Or at least until Qunicy Jones appeared in 1964 with the score to Sidney Lumet’s THE PAWNBROKER.

The Pawnbroker (1964)

Reflecting a developing black consciousness, Quincy Jones' score for THE PAWNBROKER is among the first dark drops which would eventually become a gushing sea of shiny oil. Jones' background was as a band arranger and studio producer. This meant he could combine an urban sensibility with a studied and perfected European-style mode of orchestration. Many moments in THE PAWNBROKER deftly slide between the two.

While the score bears tonal shades reminiscent of the brassier moments in Duke Ellington's breathy jazz score for Otto Preminger's 1959 film, AN ANATOMY OF A MURDER, Quincy Jones pushes THE PAWNBROKER past jazz into a a wider net of styles. Ellington's score is a seamlessly woven jazz text which embodies the film's narrative wholly. Jones' score declares its displacement clearly – like a Jew in Spanish Harlem (a la Rod Steiger's character) or a black on the Hollywood soundtrack. The main title's use of vibes, celeste, harpsichord and harp tantalisingly cast semi-jazz clusters against a monophonic semi-blues line played by thickened strings. It's like hearing Duke Ellington and George Gershwin simultaneously. It's black; it's jazz; and all the space between.

In another sense, THE PAWNBROKER is also funky. Not as in the percolating rhythms we normally associate with funk music, but 'funky' in the deeper African-American sense: a heady brew of extreme contrasts and polyglottic textures which celebrates Otherness. Throughout THE PAWNBROKER, that 'melting pot' of which American culture is so proud is alive, breathing and sweating. Latin percussion, fusion-style alto sax solos, be-bop double bass, freestyle drum kit bursts, atonal organ lines - all capture the mulatto melodiousness of the real and mythical New York street. No aural homogenisation is apparent; multiple instrumental voices are allowed their distinctive presence in the arrangement and the mix.

The Deady Affair (1967)

It might sound like cheesy cocktail jazz but it isn’t. It’s Quincy Jones’ score to Sidney Lumet’s 1967 film THE DEADLY AFFAIR. Like so many Hollywood composers, Jones covered everything from soul to rock to bossa nova. But his orchestrations and arrangements reveal an advanced musical ear. Jones knew how to breathe life into any popular idiom.

Jones was one of the few black composer/arranger/conductors of a serious bent who dreamed of the concert hall but found cinema to be a more accessible stage. Yet while he occupies a clear position within Jazz especially and the recording industry specifically, his role as a black composer of film scores needs to be put in context. Jones himself stated the problem clearly: He said, “Blacks couldn’t write string dates. They wouldn’t let you. You could only write for big bands.” So for Jones and many other black composers, orchestrated film music was unofficially deemed a pursuit for those with clear European heritage.

This Euro-version of black music has its own history in Hollywood. Not allowed but incapable of being suppressed, blackness is felt as muted sub-sonic waves on many soundtracks from the 30s and 40s. From the smeared jazz of gangster movies to the mottled R'n'B of Broadway musicals, African-American music squirms like dancing insects under Hollywood's Caucasian blanket of fiction. Many dismiss these early scores as unauthentic tracings of 'true' black music. But the irksome pseudo-jitterbuggery which peps those scores should be regarded as Hollywood's inability to stem the sono-musical swell that is black music: offensive to the cultured taste-buds of the time yet too impressive to be aurally absented. This is the ‘blackness’ that fuels Quincy Jones no matter how pale the music appears.

In Cold Blood (1967)

Richard Brooks’ 1967 film IN COLD BLOOD. A groundbreaking movie in its depiction of the fatal arc that shapes the outline of an unbalanced and violent crime. Jones’ score is a rarity both then and since in its sympathetic portrait of the one of the film’s disturbed killers, whose background includes child abuse, orphanages and juvenile hall. Jones in this film employs the multi-voicing of jazz to represent schisms and contradictions in the killer’s psychological make-up. A pathological and uncontrollable force, the killer is also a child trapped in an aberrant mind. Jones conveys this not through atonality, but through a discomforting simultaneity, expressing the irreconcilable differences operating in the modern social mind.

In The Heat Of The Night (1967)

In the 9 years between 1964 and 1972 alone, Quincy Jones composed music for 40 films. This was his most concentrated period. It also is an era that defined an emerging 'sound of the city'. In crime films of the time, the city is a harsh, violent environment, where racial and criminal tension is tauter than any violin a soundtrack could record. Jones was pivotal in defining this ‘sound of the city’. Strains, glimmers and blasts of soul, R'n'B, blues, jazz and funk are blended into a beautiful din in his urban scores.

The city for Qunicy Jones is neither location nor myth. It is a living history of racial crossovers performed in and beyond the name of Jazz. Jones’ collective works embody the traffic coming from both sides of town. One can hear the organic pointillism of Duke Ellington’s chords laid across diverse instruments. One can also hear George Gershwin’s symphonic transformation of slight blues figures into epic jazz monuments. Quincy Jones lives in their city – but colours it in wide-eyed black and white. Nowhere is this more apparent than in his score to Norman Jewison’s 1967 film IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT.

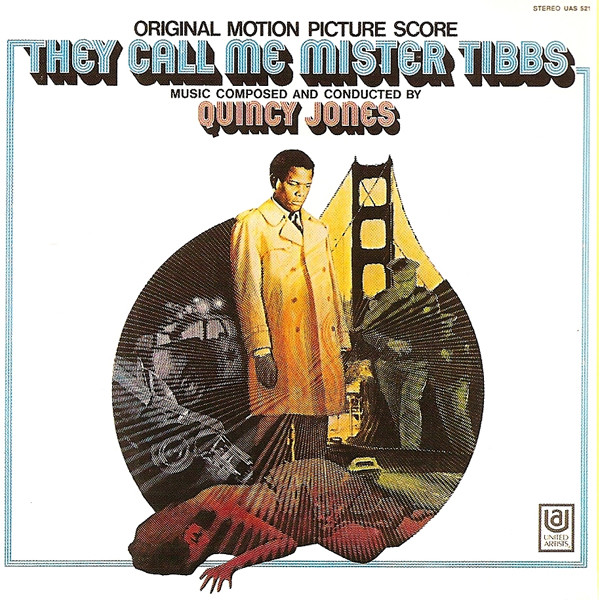

They Call Me Mister Tibbs (1970)

The sequel to IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT was released 3 years later in 1970, directed by Gordon Douglas. Titled THEY CALL ME MISTER TIBBS, it was a vehicle for both Sidney Poitier as actor and Quincy Jones as composer. As with all his scores, Jones arranged his music with specific performers in mind. In place of national symphony orchestras, Jones’ music is performed by ensembles of his selection and formation. THEY CALL ME MISTER TIBBS is Jones at his funkiest, bringing together an array of full-blooded session musicians whose distinctive identities brand the score as jazz. It’s a great example of Jones’ flexibility – composing by producing, arranging by conducting, orchestrating by performing.

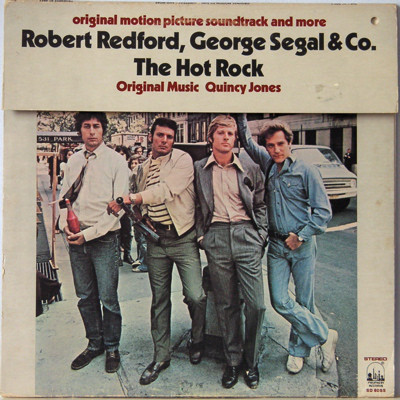

The Hot Rock (1972)

THE HOT ROCK, directed by Peter Yates in 1972, is one of near hundreds of heist movies made in the early 70s. All heist films had the obligatory theft scene, usually played out in tense silence and tantalizingly fragile music cues. Jones was a key figure in creating the musical tension many people identify with these films. His 20th Century ear borrowed and reworked much from Edgar Varèse’s impressionistic studies of the American desert, where percussion embellishments were brought to the fore. Varèse was liberating percussion from its non-musical status. But for Quincy Jones, percussion needed no such liberation: it’s the pulsating blood of Pan-African music.

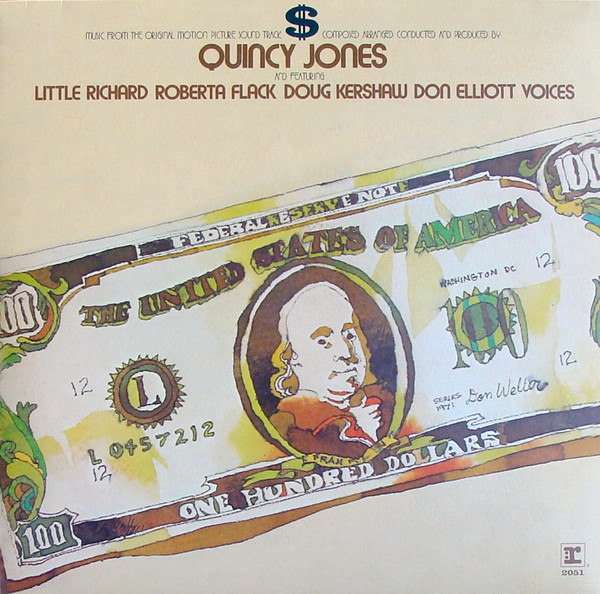

Dollars ($) (1971)

Richard Brooks’ 1971 film DOLLARS ($) is another heist movie with another score by Quincy Jones. But this is one of his most idiosyncratic scores. It features the unclassifiable Don Elliott Voices. In reality the dextrous and delirious multi-tracking of a single singer – Don Elliott – the Don Elliot Voices create a sound somewhere between the Andrew Sisters and Gyorgy Ligeti. It’s a wholly unreal sound, and one typically shaped by Jones and his sharp ear for the style of playing his performers bring to his scores. He succinctly described this approach: “My instrument is playing the musicians.”

Beyond the traditional jazz format of merely spotlighting soloists, DOLLARS ($) exemplifies his archly modern take on integrating the performer into both score and mix. As producer, Jones has always controlled the phonographic aspects of his recordings – more than most composers in both classical and jazz traditions. Microphone placement, studio acoustics and mixing technique are as equally part of his craft as those skills normally associated with composing music. The end result is a palpable energy that celebrates both musicians and their instruments while creating music that will exist only as a recording on the soundtrack.

Outro

Film composer Qunicy Jones. Lost in history, but still living in the grey zone between defiantly egocentric jazz improvisation and the Eurocentric grandeur of tonal orchestration. Jones’ writing, arranging and orchestration belie an overlooked complexity. With cool verve and bold respect, Jones wrenched the film score from its Wagnerian cave and slammed it down in the midst of cross-town traffic, where horns are sounded by cor anglais and cadiallacs alike.