Background

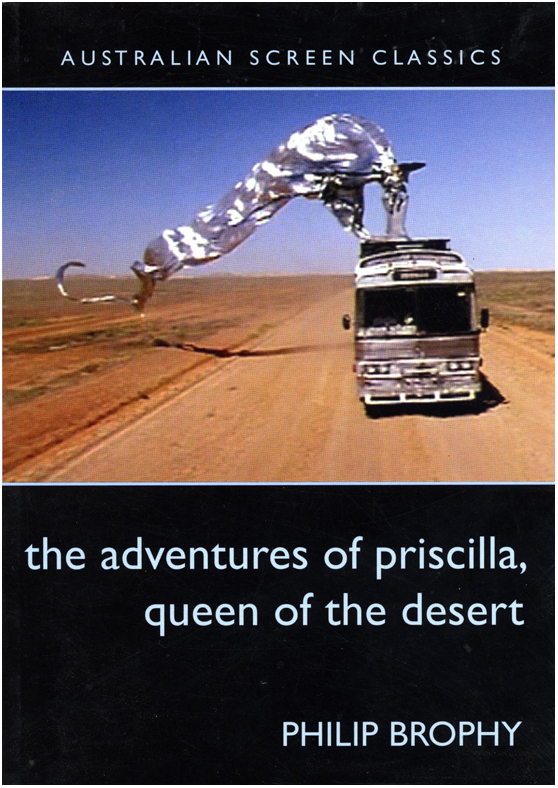

Part of the Australian Screen Classics series, The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert was commissioned by the series editor, Jane Mills for Currency Press and the National Film & Sound Archive.

The book may not be for lovers of the film or for patriotic lovers of Australian film culture ...

"How liberating to have a film full of mincing queens prancing across the charred central Australian landscape. How radical to throw up gay culture onto the big screen in the most mainstream limelight of cinema. How universal to have a film whose story reaches beyond sexual stereotypes. Such are the myths that strangle Priscilla like a feather boa caught in the mag wheel of the film's gloriously vulva-hating machinery. A perfect Australian film in so many respects, Priscilla beautifully swirls this country's sexual confusion, appropriated landscape, heroic delusions and colonial scars into a delirious dance of numbing normality. Freely interpreted this way, Priscilla becomes an otherworldly tale of silver colons, feminine stench, acidic voices and musical bile. Swallow it down whole."

The Priscilla book came into being thanks to the perceptive persistence of editor Jane Mill who accepted such a thoroughly un-Australian reading of the film. No thanks is due to Currency Press, who published the book but now refuse to list it in their catalogue.

2016

EXPERIMENTA SOCIAL - "Terra Nullus & Priscilla" slide talk, ACMI-X, Melbourne

2008

Published by Currency Press, Sydney

Overview

Introduction (from the book)

Picture those 17th Century maps of white Australia with names like Terra Australis and New Holland. They appear ill-formed, misshapen, like an embryonic blob sliding to the bottom of a sphere. Yet at their inception, those maps were plausible cartographic tracings of how a ship would circumnavigate the perimeter of a land mass so as to deduce its continental form.

To the modernised eye of white Australia, those maps are wrong, quaintly so. Not because their cartographic impulse nullified the extant territories inhabited by indigenous people, but because white Australia has had its ratified shape burnt into its collective retina. Its fusion of continent, map and logo sums up Australia as a mass - an island to itself; an identifiable shape; an ideogram prompting recognition; a brand promoting jingoistic consumption. Its semiotic directive encourages Australians to perceive this thing called 'Australia' as a whole to which one's partial self can be attached and attributed.

By extension, anything labelled 'Australian' is aligned with this logoistic enterprise. Most things 'Australian' are pre-labelled and self-proclaimed so as to enforce cultural associations, rather than nurture discovery or allow repulsion. In this respect, Australian icons are like botanical and zoological specimens, categorised as being emblematic of 'Australia' in order to prove the uniqueness of the Australian continent. Australian cinema has developed along these anthropological lines. It blares its 'Australiana' to anyone within range, lest they feel beached upon a continent with which they cannot identify. Like verified cartography, corrected terminology, validated morphology and classified iconography, 'Australiana' on screen is a desperate recourse to circumnavigate an Australian consciousness and prove its whole, its mass, its collectivity.

This book is a reading of a map. The map is the 1994 film The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert - herewith referred to simply as Priscilla. The film tells the story of Sydney drag queen Mitzi/Tick (Hugo Weaving) who has been offered a gig at a small casino in Central Australia, run by Mitzi's ex-wife Marion (Sarah Chadwick). She wishes to take a break, and the situation provides Mitzi with the opportunity to break free from his depressing life in Sydney - and to re-acquaint himself with their son Benji (Mark Holmes) whom he has not seen since coming out and separating from Marion. Mitzi enlists two other drag queens to travel with him and perform at the outback casino: the aging, acidic transsexual Bernadette/Ralph (Terrence Stamp) and the young, precocious toy boy Felicia/Adam (Guy Pearce). The cash-strapped trio purchase an old bus which they christen Priscilla Queen of the Desert, and haul themselves west into a world devoid of urban sophistication and liberal sexual attitudes. Through a series of emotional highs and lows, they forge their road trip, meeting colourful locals and encountering volatile predicaments, and therein discovering something about themselves. The story concludes with Bernadette staying in Alice Springs with a new admirer, the elderly, macho Bob (Bill Hunter), while Mitzi and Felicia return to Sydney rejuvenated. Mitzi finally bonds with Benji, who inspires his father by being comfortable with his dad's sexuality.

To some, Priscilla is a thoroughly familiar movie, full of uniquely Australian sentiment and perspective. They would see gay role models, moving comedy-drama, beautiful landscape cinematography, a wonderful camp sensibility, celebrated Australian stereotypography, and an international film success that "blitzed overseas box offices" and "caused a near riot at the Cannes Film Festival" (according to the 2004 DVD hyperbole). To me, Priscilla is as alien as the landscape that greeted the first convicts, prospectors and settlers. Across its terrain, I detect quite different things. I hear the off-station broadcast crackling of David Bowie's "Let's Dance" and Sister Sledge's "We Are Family". I see a host of movies whose apparition are likely to have been invisible sprites to many: Sextette, The Man Who Fell To Earth, The Boy Friend, Cruising, The She Creature, Thelma & Louise. I flick the unlocked channels to pick up transmissions of John Mellion's Victoria Bitter television ads, the Opening Ceremony of the 2000 Olympic Games, the Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras, 3 episodes of the Australian Queer Eye For The Straight Guy. By reading Priscilla as a map, I survey unlikely national formations, hidden bodily topographies and polysexual voices, sounds and images.

By reading Priscilla more than merely watching it, I forthrightly accept all the wrong mapmaking which locates the film - and every other successful Australian film - within a triangulated perspectival plane formed by Australian identity, Australian culture and Australian cinema. Australia particularly celebrates the celestial alignment of those three axes from which vantage point the nation can lay territorial claim to 'getting it right'. For some, my reading of Priscilla will be as woefully wrong as those early maps drafted by Janszoon, Cook and Flinders. And hopefully so, for my intention in this reading is to get as much as wrong as possible.

What you are about to encounter is less an analysis of the film's dramatic script and its visual narrative, and more an assessment of the signs circulating within the movie. I leave others to discuss director Stephan Elliott as an Australian auteur, the film's performers as gay icons, and the overall artistry and popularity of the film's production. In as much as Priscilla is accepted as indelibly Australian, my reading will follow the film's nation-building road-trip as a meandering road-map leading to colonised, territorialized and localised incidents of this thing called 'Australia'. I take you on no journey - only a series of disjointed passages; some interconnecting, some regenerating, some negating. For rather than championing Priscilla's undisputed international success across 1994 and 1995 and its consequent enshrinement in the living museum of Australian iconography, my reading of Priscilla celebrates the great nothingness of white Australia and all the heady delusions and spindly neuroses which atmospherically circulate around its engorged mass.

If my reading is deemed contentious, it is only because such a low threshold persists for critiquing Australia's nationalistic neuroses - particularly in its movies. A 'dumb semiotics' has been fostered in Australian cinema wherein 'Australia' seems bent on seeking itself out, fawning over its cosmetic make-up, and supposedly discovering its identity. Yet the 'reading' of Australiana remains illiterate, ignoring the multi-layered levels of signification enlivened by semiological analysis and its linguistic practice of multiple readings and lateral associations. In cinema, this dumbness has been shaped by envelopes of pressure born of legislation (economic, sociological, political, ideological) and myth-making (the undying journalistic championing of any base-level success Australia enjoys on the international platform). The result is a national cinema that frightfully - indeed, viciously - directs iconic representation and symbolic signification toward a funnel for extracting an 'Australianism' whose elixir supposedly informs, entertains and engages by producing Australian stories for Australians.

By virtue of its substantial success, Priscilla is a drop formed by that elusive elixir. My purpose is to re-ambiguate Priscilla by pondering the atmospheric conditions which determine its audiovisual signage. My map-reading is thus derived from sensing, sounding and tracing the semiotic verticality and iconic stratification distributed throughout the film. By getting wrong all the directed signifiers that drive the film toward its affirmation of Australian identity, a refluxive momentum will be established from which the film's sounds and images can be connected to a larger cultural terrain which does not automatically honour Australia. This reading, then, is irrefutably un-Australian. It is less concerned with how the film reflects local concerns and national aspirations, and is more concerned with how the film can be connected to international and transnational concerns. Not to be confused with 'Aussie-bashing', my reading of Priscilla yearns for an escape from this thing called 'Australia'. In place I suggest ways in which Australian cinema can be semiologically interpreted so as to open up ways in which Australia reflects itself and refracts all beyond its shores.

And beyond the film's shores we shall go. We will be sent uncontrollably to - among other things - screaming queens and silenced hags; chrome-plated buses and chrome-plated logos; rotating mirror balls and flying ping-pong balls; the Snowy Mountain Water Scheme and Watarrka National Park; wog boys and gay boys; lip-synching and post-synching; ABBA and Kylie; Rolls Royce's Spirit of Ecstasy and bad pup XTC; vaginal expulsion and colonic propulsion; Isadora Duncan's flowing scarf and Al Pacino's leather jacket; smelly fish and fragrant women; Asian brides and Aussie battle axes; slabs of XXXX and abs like 6-packs; ugly Australians and New Australians; bad house music and bad film music; transculturals and transsexuals. We will encounter self-loathing, self-hatred, self-immolation and self-annihilation.

For those who want to see themselves on the screen - you are likely to find yourself here. By the busload, like strangers in your own strange land, you can gawk at the image Australian cinema continually projects to you. Consequently, my reading forms itself into a palindromic text, playing Priscilla backwards to you in its celebration of being Australian. Yet not once will I debate the film's professionalism, execution, craftsmanship, success and popularity. Bypassing such conservative chauvinistic criteria which qualifies Australia cinema's success, my close reading will be responding to Priscilla's tonality: the weight and porosity of its audiovisual texture. It will lip-synch its own soundtrack which will not be a menu option on the DVD release.

If petty thief cum pre-gay philosopher Jean Genet had been time-warped and sent to a penal colony in Australia, then jettisoned to a far future on the eve of Priscilla's lauding at the 1995 Cannes Film Festival, he may have written a book like this one in order circumnavigate Priscilla's mapping of the gendered body, the sexualized voice and the eroticised corpus. Mind-fucked by transcultural historiography, Genet too would have been woefully out of synch with all sense of Australian cultural propriety bent on idolising the film's salacious 'bent'. In the spirit of Genet's self-degrading recoding of the obvious, my reading 'drags' Priscilla's appropriation of drag, and honours the film as an apotheosis of a unique brand of nihilistic glory in which white Australia excels.

Technical

Book contents

Prologue - Reading Maps

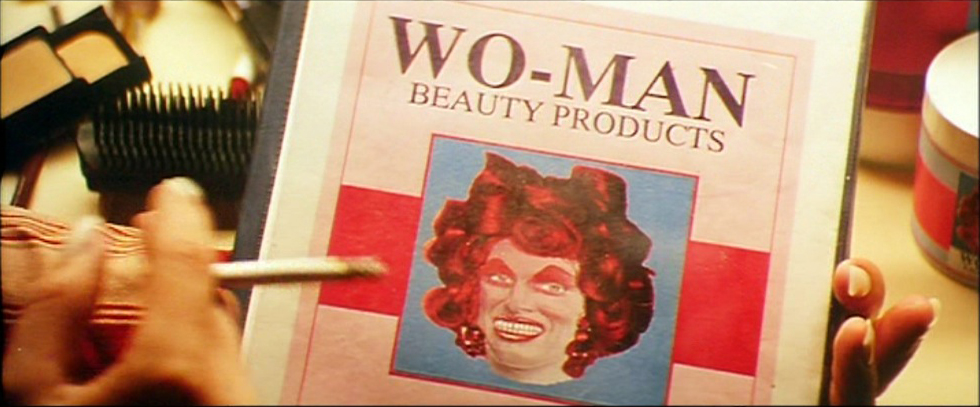

I - Silencing women

Ugly bitches. Open mouths.

Mae West. The Village People.

Inflatable sex dolls. Opera divas.

II - Synching lips

Drag performance. The musical genre.

Charlene. The male sex.

Singing. Miming. Becoming song.

III - Drinking Fire

Beer. Urine. More beer.

Alcoholic spirits. Torch singers.

The penis. The Australian accent.

IV - Staging Reality

Media advertising. Cinema.

David Bowie. Racial assimilation.

Gloria Gaynor. AIDS.

V - Doing Landscape

Indigenous land. Didgeridoos.

2000 Sydney Olympics. Bulldozing. Death.

Snowy Mountains Scheme. Mother Earth.

VI - Being Gay

Sydney Mardi Gras. Hollywood drag.

Al Pacino. Sandra Bernhard. Steve Tyler.

CHIC. Sister Sledge. Family.

VII - Making Monsters

Body radicalism. Frankensteinian process.

Isadora Duncan. The smell of women.

Asian bitches. Aussie families.

VIII - Sounding ABBA

Eurovision Song Contest. Alien abduction.

Punk. Wog disco.

Record production. Robots. Kylie.

Epilogue - Burning Maps