Reviews

Mapping an Ugly Australia

published in Real Time No.85, Sydney © 2008

by Keith Gallasch

I watched The Adventures Of Priscilla Queen Of The Desert only recently, surprised to find that for all its popular success, it’s a curiously tense, bickering, often grim fable of irresolute australian manhood—whether straight, transvestite or transsexual. It also treats its women very badly. In an early edition of Realtime (rt 4, p4), in a three-way dialogue, Jacquie Lo, Merlinda Bobis and Helen Gilbert targeted the film’s appalling account of a verbally aggressive Filipino woman, isolated in the outback, entertaining the pub locals by shooting ping pong balls out of her vagina and upstaging Priscilla’s transvestite showgirl trio. Philip Brophy addresses this moment and many more in a wickedly engaging non-linear analysis of the film that pulses with odd juxtapositions and unexpected associations connecting up disparate elements into a ‘map’ of the film and the culture it conjures and from which it has grown.

Roland Barthes wrote somewhere that denotation is the last of the connotations—we come at meaning not directly but through a host of associations. Philip Brophy is a whizz at the art of the semiotic reading of a cultural object, attentive to every aspect of its surface (its “tonality; the weight and porosity of its audiovisual texture”), its edges and layers (its “semiotic verticality and iconic stratification”) and, above all, a network of associations branching out into the greater cultural tanglewood. His is a poetic and highly rhetorical approach, relying often on the power of suggestiveness and he’s a dab hand at sly allusion and irony. Not every assertion convinces, especially when Brophy’s at his most polemic in this brisk 82 page read; dismissiveness comes too easily and some will read it as a clever dick assault on a sacred cultural object, and Australian film with it.

Writing about Priscilla provides Brophy with the opportunity to challenge the “dumb semiotics” of Australian culture and film in particular where the “pre-labelled and self-proclaimed...enforce cultural associations, rather than nurture discovery or allow repulsion.” Familiar tropes and icons are clung to in the name of uniqueness. But they are not meaningful for Brophy: “to me, Priscilla, is as alien as the landscape that greeted the first convicts, prospectors and settlers.” His map of the film, he declares, will be “less an analysis of the film’s dramatic script and its visual narrative, and more an assessment of the signs circulating within the movie.” And he knows he’ll be seen as getting it wrong: “This reading...is irrefutably un-Australian”, but not, he emphasises, Aussie-bashing, though some readers might regard that as spin: “[My] reading celebrates the great nothingness of white Australia and all the heady delusions and spindly neuroses which atmospherically circulate around its engorged mass.”

In a culture in which so little film analysis is characterful, let alone brave enough to locate film in the big cultural picture, Brophy is very much a felt presence in his little book. He announces up front that “in the spirit of Genet’s self-degrading recoding of the obvious my reading ‘drags’ Priscilla’s appropriation of drag...” He imagines a Genet “time-warped and sent to a penal colony in Australia then jettisoned to a far future on the eve of Priscilla’s lauding at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival...he may have written a book like this one...” For Brophy, ever the outlaw, imprisoned in Australian culture but always breaking out, this is no occasion for cringing humility. The writing is rich in image and metaphor, often pushing into excess to make its mark, but replete with all kinds of drollery in the tradition of the queer outsider—from Oscar Wilde to Quentin Crisp and on to Sandra Bernhard. The smart arse quips—like Roland Barthes as jokester—situates the writer in the history of queer wit rather than with Genet, but the point is taken. As well as unravelling the tangle of visual and aural associations in the film, we need to step right back from the screen to see what’s really going on.

Like his role models Brophy is constantly quotable—“the reminder of the penis is the eternal lump in the throat of the drag body”; Isadora Duncan’s scarf “brand[s] her body as a machine for movement.” There are similes and metaphors that do the job (I’ve cited some of the best and wildest below), and some that don’t: “In a prolixed manner, I am reading Priscilla here as a layer of skin covering the cartilage of the Snowy Mountain Hydro-electric Scheme’s historical formation and logistical machination.” There are moments of wonderful excess like this on the joys of sinking the piss: “Harvested like a primary crop, processed like a pandemic yeast infection, distilled into a simulated urinary liquid, prone to foaming into frothy ejaculate, the sexual aura of beer can only be avoided when one is too drunk to fuck...Its gluttonous intake gears the body into a living pissoir...one might as well piss beer while drinking urine.” There are sentences containing barely submerged song titles and passages where the semiotician lingo fogs meaning. Mostly, the book is a wonderfully grumpy entertainment that makes you think more than twice about the film and the culture of which it is a part.

Brophy doesn’t read Priscilla for us linearly; he identifies key signs and then joins the dots to cultural associations that might not have occurred to us, mapping signs into a comprehensible guide to the film’s dynamics. The map’s mostly legible and rich in sidetracks and diversions that mostly take you back to the main road. Occasionally you feel you’ve run into a dead end or fallen off the map, trying to hang onto the fit of, say, the pheromonal meaning of women’s scarves. Brophy otherwise puts the scarf to good use, getting Isadora Duncan and her strangulation into the act in his cumulative account of the film’s persistent silencing of women. Its relationship to larger sign posts points to the significance of breath and the trace of the voice. It all happens very fast, and a re-reading helps make better sense.

Above all Brophy is attentive to the sound of film (in his own films and performance, in his Cinesonic column for RealTime in the 1990s, his international conferences with the same title, and his British Film Institute book, 100 Modern Soundtracks). It’s not surprising that breath, voice, accent, popular song, opera and the didjeridu figure potently in his response to Priscilla, looping into a disturbing totality. He starts out with Shirl, a woman, alone amongst a bunch of tough but reticent blokes in an outback pub, who verbally attacks the transvestite trio:

Shirl’s open mouth is the black hole of the white void at the red centre of Australia. Her oral gape is the glassy eye of the film’s sociological hurricane: a raging whorl of misogynist energy that spins around this charade of a butch dyke...Shirl is like all nagging wives: a bitch to be shut up. And to be shut up by a British trans-sexual [Terence Stamp as Bernadette]—now that’s Australian comedy.

Brophy’s writing here, as elsewhere, is itself “a raging whorl”, sucking a host of associations into its vortex and swirling towards its destructive, knockout punch line. Then the storm starts up again slowly building to a series of coups de grâce, via discussion of the inflatable doll atop the bus, the opera soprano and the film’s breathing (the central characters “develop less through a series of trials and tribulations and more through an arrhythmic concatenation of inflated and deflated moments”). He writes, “all [the women] are defined by the means by which air fills their being. The doll is blown up, the drag queen is puffed out, and the female corpse is pumped within.” The film’s use of the opera aria allows Brophy to drive home the governing “necrotic” (his compounding of necrophilic and erotic) dimension of Priscilla while giving him room to comment on opera as drag. He sees opera “as a form of drag in the first place—a woman performing a man’s creation…Controlled by the Promethean impulse of the composer she bears his breath.” The result, Brophy thinks, is “the anodyne resonance of pure tone”, at a remove from real emotion and deadly: “For when Verdi’s aria is smelted from the hovering inflatable sex doll, death is in the air.”

It’s a short trip from opera to musical, since in Priscilla there are ‘live’ songs as well as mime. Again Brophy joins the dots between breath, voice, drag and death: “Ultimately, all Musicals are drag revues” because they use lip-synching, just as in drag mime “which creates the ghostly aura of a human presence.” Shortly, in the same terms, he addresses the drag queen’s narcissistic appropriation of the torch singer. The argument is dark and arresting but just when you suspect you’ve been lead into some semiotic back block, Brophy guides you back to the film’s central trio—and their voices.

By now, Brophy has detected that for all the film’s inflation (its uplifting horizons and aerial views) there is a prevalent depressive and necrotic deflation. On the matter of voice, he observes of the trio that “they flip between displays of tartiness and blokiness, the former with physiological ineptitude and the latter with theatrical inexactitude.” He connects the limited binary being of these men with John Mellion’s VB beer television advertisements, tourist industry images of Australia (and of much Australian film) and a persistent national ailment: “contrary to its gay portraiture, Priscilla captures the sexual confusion that foams around the churning waters of gender divisions which so desperately chart Australia’s ongoing frontier roughness and the brute ways in which male and female are cleaved from the other.” Never mind the clunky metaphor mix, Brophy’s point is clear—while the film might throw up a mass of complex associations, it’s still represents a “dumb semiotics”, un-nuanced, un-gay and deeply prejudiced.

Priscilla, like many an Australian film for Brophy, has ignored alternative voices, appropriated and transformed them into standardised Australian signs, sucking the breath out of difference. But gay culture itself is also problematic: “Post-70s, gay culture’s officiated alignment with notions of ‘pride’ and ‘community’ effectively closed off the perversity of a pre-gay epoch. In the process it partially normalised the aberrant power born—no matter how problematically—from exploring identity potentiality beyond the barriers set by heterosexual identity.” This culture is now progressively de-queering a unique heritage: “Far from being oppressed, hamstrung or constricted, sexual identity in early to mid-20th century gay subculture was utilised as a proto-totemic signifier ripe for subversion, inversion and conversion.”

Up to now Brophy has written little if anything about Australian film composition and sound design. Now with apt perversity, he’s taken on a film he dislikes in itself and for what it represents about Australian film and culture and does it bizarrely great service, if nonetheless condemning it for the crude binarism of its dumb semiotics. He has discovered that “[t]he film is a labyrinthine text, honeycombed with signifying pathways fragmented by multiple modes of performance and characterisation...” He is taken with Priscilla’s music: “I find that the innate novelty, studio trickery, sonic complexion and lurid narratives of nearly all the 70s songs dragged in and throughout Priscilla create a lasting aural depth within the film’s audiovisual assemblage…as if the cinematic veneer of its construction cannot contain the energy of the songs and their original performance.” In the end Brophy wonders, “maybe the phenomenon of Priscilla has little to do with cinema.” Its appeal resides everywhere else in the cultural map of which it’s part but not in the film itself.

For Brophy, The Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert turns out to be a treasure trove of songs and other cultural signage—the good, the bad and mostly the ugly. The bottled turd of Agnetha (of ABBA fame) epitomises gay and straight male misogyny, the treatment of the Filipino, Cynthia, is “one big gang bang”, the attitude to Aboriginal people is assimilationist and the musical finale with the trio dressed as Australian native fauna is a performance which “remains nothing but inhuman, as they shift representation of Woman to a series of animalistic, reptilian and monsterised figures.”

But the film has worth, it seems, if only as a mirror image of our culture—one which has to be read with the Brophy map in hand: “Priscilla’s straight eye on a queer world grants us the most potent symbolic condensation of this uniquely Australian self-distorted portraiture...this dark jewel of popular culture is a mystical stone which especially grants male Australia the power to see itself for what it really is.”

Brophy’s book is a challenging read, in the best sense, and good fun, witty and instructively gross by turns. My major reservation is that the only other Australian feature film mentioned (also disparagingly) is Muriel’s Wedding and there’s a passing reference to several outsider films: Wake in Fright, The Coca Cola Kid and Where The Green Ants Dream. Brophy’s blanket reading of all Australian feature film as locked into the nationalist syndrome is wearyingly absolutist for a writer who otherwise reads film and the world complexly, but don’t let this deter you from a scintillatingly good read.

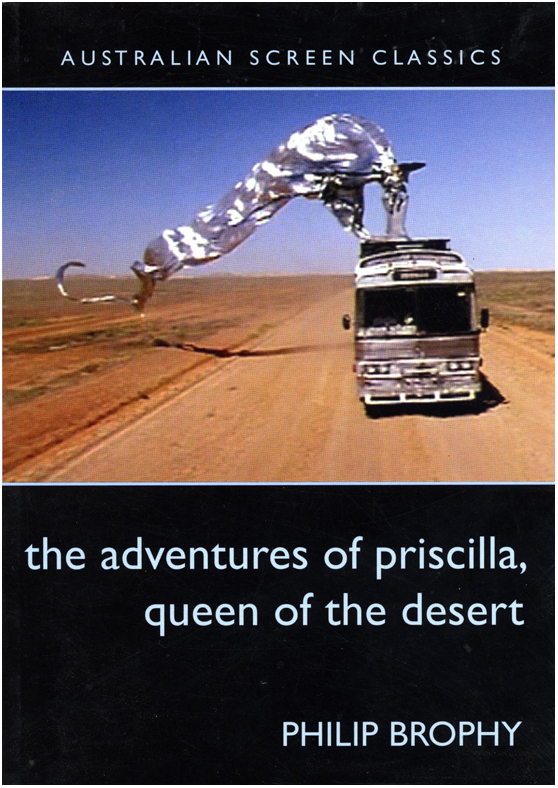

Jane Mills, the series editor of Australian Film Classics, made one of her best choices in assigning The Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert to Philip Brophy. As with most of the series to date she has wisely avoided predictable choices, reaching beyond the industry itself, the academy and reviewers. I’m looking forward to the latest instalment, Henry Reynolds on Fred Schepisi’s The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith.

The Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert

published in Australian Book Review No.303 July-August, Melbourne © 2008

by Brian McFarlane

Film-maker Philip Brophy, probably still best known for the cult horror movie Body Melt (1993), presents a provocative take - or series of takes - on Stefan Elliott's The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994). The book scarcely constitutes an introduction to the film: it almost counts on the reader's having done some serious thinking about the film before coming to grips with what Brophy offers. You are not in for, say, an auteurist reading or a cultural studies contextualisation.

The prologue announces at once an idiosyncratic stylist. Dissociating himself from conventional readings of the film, he proclaims firmly: 'My purpose is to re-ambiguate Priscilla. (Did he make up 'ambiguate'? I've never heard it before, but plan to use it again.) What emerges is not a clear linear reading of the film, but 'more an assessment of the signs circulating within the movie'. Those with fond memories of Priscilla as exhilarating road movie cum camp extravaganza should prepare to re-affectionate those memories on different grounds.

The study opens with an analysis of the image of Shirl, the outback pub habitué whose crude homophobia attracts from one of the three queens the famous riposte about the only way she'll get a bang. Brophy writes: '[Shirl's] oral gape is the glassy eye of the film's sociological hurricane: a raging whorl of misogynistic energy that spins around this charade of a butch dyke.' Thus, he locates the way the film goes about 'the silencing of women', and goes on to interrogate its representation of gays and women and 'Malestralia'. His unifying motif is the concept of 'reading a map' of early Australia: the film is as unconducive to a collective liberal reading as those early maps were misshapen when they tried to come to terms with the white sense of a new land mass.

Brophy undermines notions of Priscilla as a feel-good film. It may, he claims, 'flaunt gay visuals, but every time the conflicted queens open their mouths, the film reveals itself to be as macho as the Victorian Bitter advertisements'. That is an example of the kinds of contradiction that Brophy sees feeding into the film's tortured generic and ideological complexities and confusions. As a musical, he finds it undercut by its 'unrelenting nihilism', fired by 'self-loathing' as this 'labyrinthine text' is. Does that sound like the Priscilla you remember?

One of the strengths of the book is its wildly eclectic intertextual references. Brophy's achievement is to make Priscilla seem a richer experience by his wide-ranging excavations beneath the film's gaudy surface. The book constitutes an attack on the liberal mouthpieces of Australian culture whom he would dismiss for their homogenising labours which suppress the dissident elements in the cause of identifying a collective 'Australiana' at work.

Brophy's language, sometimes over-ornate, won't be to everyone's taste. The illustrative stills are smaller than one would like and a bit muddy, and there are surprising typos. Maybe you'd like a clearer guide through the film's journey, but you won't often have so many stimulating landmarks pointed out along the way. Not having seen Priscilla since it first appeared in 1994, I now feel that I only half-watched it and have less-than-half thought about it since.

The Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert

published in Screening The Past No.23, Melbourne © 2009

by John Conomos

Philip Brophy’s The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert is a most welcome tour de-force addition to Currency Press’s Australian Screen Classics, which is edited by the indefatigable film scholar-activist Jane Mills. The series’ editorial charter is to commission distinguished authors and thinkers from the diverse worlds of art, culture, criticism and politics to write on Australian cinema. Such a series of monographs on Australian film culture has been devised to produce polemical, provocative essays that will – hopefully - make us discursively reflect on who were are as a nation, on our culture, history, and our past and present films.

I say ‘hopefully’ because seldom do we encounter these days insightful, boundary-expanding film criticism and scholarship that is as inventive as cinema can be. In this critical context, Philip Brophy, artist, film director, lecturer, composer and animator, amongst other things, has written an extraordinary multifaceted critique of Stephan Elliot’s classic 1994 The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert. Philip Brophy, a prolific hybrid, a-categorical artist-thinker-filmmaker, has penned a brilliant, scorching, bravura polemic – one of the best that I have read in recent years on Australian film culture – on a key 1990s film and an iconic phenomenon that is so (alas) predictably categorical, formulaic and indicative of our cultural demons, obsessions and limitations as a national film culture.

Brophy’s monograph is a warts-and-all ‘love letter’ to all of us who reside in this country. His telling dedication is ‘for Australia’ and, make no mistake about it, he sincerely means it. It is a ‘love letter’ in the surreal (risk-taking) sense, as meant by David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (USA 1986). A ‘love letter’ that asks us, as his readers, nothing less than to check out our own aesthetic and cultural baggage, as individuals and as a nation. The question is, do we have the hermeneutic and existential courage to do so?

We are informed, in Brophy’s acknowledgments, that it is also dedicated to the late Paul Taylor, the art and cultural critic, whose ‘spirit’ Brophy felt as he wrote this necessary iconoclastic, scathing and playfully poetic reading of a particular map (viz. Priscilla). But here we have the basic paradox that animates this book - Brophy is a cartographer, a paratactical writer, a tracker who puts his ear to the ground beneath him and hears the seismic fault-lines and tremors of our national consciousness as it is represented in the film’s audiovisual atmospherics, concerns and signifiers that speak of ‘Australiania’. It is that creative, cultural and semantic fog that has been constantly seeping throughout our films, and our audiovisual culture, since the start of the last century, crippling our cultural art forms of representation-production. It is that deadly compulsion of ours to create in that tiresomely unimaginative and stereotypical formula of Australian identity, Australian culture and Australian cinema. When will things change? It is in this critical sense that Brophy’s book is resolutely ‘un-Australian’. And we are thankful that it is so. If this was America in the 1950s, Brophy would be pleading the first amendment to Senator Paul McCarthy!

But let me be clear here. Brophy is not engaging in ‘Aussie-bashing’, for what motivates his spirited diagnostic and intertextual polemic is his fiercely independent spirit of poly-generic critique, scepticism and passion, acting like a ‘go-between’ (Serge Daney) between art, cinema, culture, music, and theory. For Brophy’s most important agenda is to ‘drag’ Priscilla out of its engorged audiovisual miasma of cultural, gender and performative stereotypes, logo–brand concerns, nationalistic myths and our persistent non-cinephilic obsession to forge ‘quirky’ films that mindlessly celebrate being Australian. Whatever that may have meant back in the last century and whatever it might mean now.

So, Brophy’s motivation as a commentator on Priscilla, and Australia cinema, in general, is it to take the film beyond the ‘fatal shores’ of our island-continent into the broader global context of international and transnational concerns. Brophy’s witty and pun-encrusted project is to transcend the film’s national concerns and open it up to a more dynamic poly-cultural and intertextual reading of the signs that are characterising the film’s aesthetic, cultural and conceptual architecture.

This means criticising our destructive obsession in trying to get a ‘correct fit’ between the dramaturgical, formal and stylistic concerns of a movie and our nation-building desire to project ourselves to ourselves, and to others, as celebratory ‘happy-go’ lucky laconic people in a country that is riddled with nationalistic ‘terra-nullius’ neuroses and myths.[1]

Brophy reads the film against its self-congratulatory, comedy-drama camp sensibility and related ‘beautiful landscape cinematography’, to reveal its stereotypical, audiovisual signage as being grounded in an all-encompassing self-annihilation, self-hatred and self-immolation.

As we traverse the film’s one-dimensional life-world of screaming queens, chrome-plated buses and chrome-plated logos, silenced ugly hags, machismo pub culture, gay and wog boys, Isadora Duncan’s flowing scarf, rotating mirror balls, the Snowy Mountains Scheme, post-synching ABBA and Kylie, 2000 Sydney Olympics, inflatable sex dolls, drag performance, beer, urine, David Bowie, Asian bitches, bad film music, etc., we encounter – time and again – our appalling inability to portray ourselves (self-reflexively) on the screen beyond the usual reductive symbolic ‘dumb semiotics’ of gross caricature, subcultures, monstrous drag, and distorted gender, national, and political myths.

So many of our ‘BBC talking-heads’ and tourist bureau inflected movies set out across our seven seas as if they are bland televisual advertisements, or official white paper policy statements, in grossly distorted national self-portraiture. It is cinema that is so tragically bereft of any sense of its own ‘mongrel ‘ origins, concerns and history. It is cinema as cinema in terms of its own fleeting fragility, materiality and suggestive poetry and not as an Orwellian billboard about our own insecurities concerning Australia, its history, image and status in the world. Brophy’s claim that our cinema is substantially warped by its own ‘Siamese twin’ viral preoccupation with television advertising is tellingly right on the money. So many of our movies are bloated in their own precious self-importance and banalities. To put it in the terms of the late American film critic-painter Manny Farber, many of our contemporary movies belong to his “white elephant art” and not, lamentably, “termite art”.[2]

Brophy’s dazzling self-reflexive map-reading of Priscilla is geared to delineating a much larger cultural terrain than what is represented in the film’s exhausted symbolic deployment of national aspirations and local concerns that is grounded in its affirmation of Australian identity. It is a cultural terrain that does not honour Australia as such but denotes a critical, transgressive, playful overhaul of the film’s nationalistic atmospheric conditions and iconic stratification. Brophy’s book is a joy to read. Here is a critic who writes caringly for the cadence of a word and, in doing so, remains at the same time faithful to the dancing transitory and multi-suggestive textures of the movie image. He is, undoubtedly, one of our finest sentence stylists and perceptive critics writing on cinema (amongst many other subjects) in this country. We can all profit from reading this most needed and provocative ‘bitter brew’ of a book that sings with many essayistic insights concerning Elliot’s popular successful film and its related cultural effects in the 1990s and beyond. I sincerely hope that Brophy’s book is in all of our municipal, school and university libraries; especially the library at the Australian Film, Radio and Television School.

It is an invaluable rubik’s cube of a book that speaks to us of many wise and dynamic things that are salient to our lives as artists, authors, filmmakers, educators, spectators and citizens who care about cinema and its ongoing aesthetic, cultural and existential potential to help us make sense of our one shared world.

Notes

[1] For a very recent lively discussion of the role of luck in our Anzac national–building narrative of Australian character see Ann Summers, On Luck, Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 2008.

[2] Manny Farber, Negative Space. New York, De Capo Press, 1998. See Farber’s essay “White Elephant Art Vs Termite Art”, pp. 134-144.