Naoki Urasawa

Naoki Urasawa

20th Century Artist

published in Madblogs, Madman Entertainment, Melbourne, July 2014Naoki Urasawa’s early manga fits the expected picture of a manga artist working in a known genre and delivering new twists with noted success. Yawara! (1986-1993) was a long-running character study of a young girl destined to be trained as a judo champion despite her desire to remain ordinary. It was an innovative twist by ‘normalising’ the popular mystical manga genres depicting high school kids thrown into wild and catastrophic dimensions due to their forgotten blood lines, which had centuries earlier decided their fate. In Yawara!, the pressure comes from the girl’s cranky grandpa who wants her to realise a dream of his making more than one of her own. It’s a very Japanese legacy: undertaking one’s heritage despite one’s identity – only to discover that one’s true identity is in fact that legacy.

But Urasawa’s latter work progressively analysed this dynamic. In particular, he reflected on how his generation became embroiled in its own turmoil of self-identity. Urasawa came of age in the mid to late 60s. It’s a special era in Japanese social history, mainly due to Japan’s phoenix rising from its post-war ashes. Two key events are symbolic of this transition: the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, and the 1970 World Expo, held in Osaka. The former coincided to an extent with Japan’s phenomenal rise in the design and production of its electronics industry. It’s a moment well documented in histories of the nation’s economic miracle. But the second event is less actual and more fantastical. The World Expo provided a grand site for Japan’s dreams of its own future. To an extent, all World Expos do this, but the Osaka Expo left a huge impression on the millions of Japanese who visited the site.

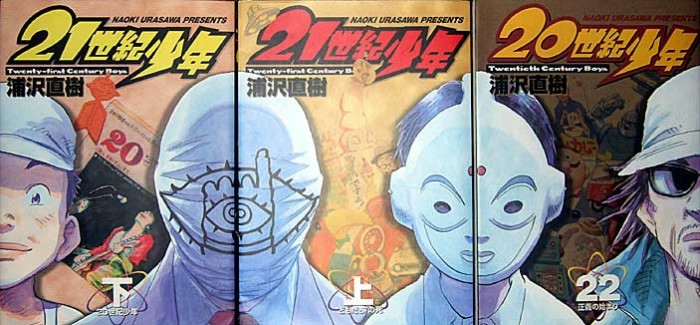

If this sounds familiar, it might be so because you’ve read some of Urasawa’s greatest work, 20th Century Boys (1999-2006). The series is a dense and methodical breakdown of how that period of the blooming Japanese psyche left indelible effects in different ways upon different people (represented by a group of young kids at the time). The success of this manga (including its translation into a live action film trilogy) is a testament to the resonance it holds for many Japanese who perceived how Urasawa crafted an engaging conspiracy tale which reverse-engineers all the futuristic visions and dreams of the Osaka Expo. In the West, the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing had a major impact on ‘future dreaming’ for kids of a similar generation in America. In Japan, the Expo’s sprawling display of advanced visions for a technological Japanese society laid the groundwork for imagining how to build a future on earth.

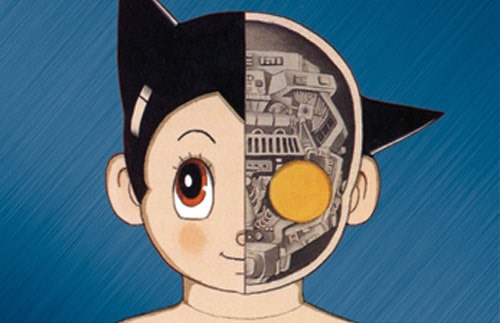

Urasawa was not the first manga artist to reflect on this. Indeed, 1960s Japanese tokusatsu kaiju eiga (special effects monster sci-fi films) constitute a vast repository of wonderful and delirious visions of living in the future. These films (particularly the film and TV cycles of Godzilla, Gamera and Ultraman) are a fanciful yet disconcerting amalgam of nationalistic couch-sessions and unbridled technological optimism. Concurrently, Osamu Tezuka’s sci-fi manga (Astro Boy, Phoenix, Wonder 3, Song of Apollo, etc.) investigated how Japan’s future could heal or open the scars of its war-torn 20th Century. This vast nabe pot of speculative fiction and futuristic production design left a huge impression on the artist Takashi Murakami. He went so far as to develop a theory of how integral this period was in the shaping of visual imagination for a generation who came into professional practice after the Bubble era (early 90s). Thus, Murakami not only introduced much of otaku sci-fi geekdom to the West: he also claimed the importance of this pop culture to a generation of painters and designers working in fine art, manga and anime.

Urasawa is clearly of this grouping, and 20th Century Boys is as sophisticated a take on these ideas as Murakami’s. Indeed, maybe more so, as Urasawa is working from the inside of this culture. It’s this interior perspective that so deftly shapes autobiographical incidents into mind-boggling conspiracy theories. It doesn’t take much to discern the imprint of everything from the late 60s Shinjuku student riots and their links to the Japanese Red Army Brigade, through to the Aum Shinrikyo sect’s attraction to ostracised otaku resulting in the sarin subway attack of 1995. 20th Century Boys is as riddled with the micro-psychological dysfunction of the Japanese psyche as the most high-brow literature. That’s the true power of manga – being capable of straddling pop culture with complex perspectives – and Urasawa wields it well.

Text © Philip Brophy 2014. Images © Naoki Urasawa, Takashi Murakami, Tezuka Productions & Expo 70 Committee