Explosive Animation from America & Japan

Published by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney - 1994KABOOM! Explosive Animation from American & Japan was a major exhibition curated by Philip Brophy and commissioned by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney in 1994. The approach of the exhibition was to draw 'postwar' connections between America and Japan and find deeper resonances in the post-atomic effects which have conjoined both countries' popular culture since. The curatorial concept was to define an 'explosive' aspect in animators' work, generating cultural perspectives that distinguished their modern/postmodern appeal from the classical tradition exemplified by the Disney studio's legacy.

Essays

-

Storming the Ramparts of Childhood

Personality, Cartoons & Other Considerations

Irving Gribbish

Titles referenced: works by the Fleischer Brothers, Chuck Jones, Walter Lanz

Titles referenced: works by the Fleischer Brothers, Chuck Jones, Walter Lanz -

No More Mickey-Mousing Around

David Sanjek

Titles referenced: One Froggy Evening, songs by Raymond Scott, The Three Little Bops, Rhapsody Rabbit, What's Opera Doc?

Titles referenced: One Froggy Evening, songs by Raymond Scott, The Three Little Bops, Rhapsody Rabbit, What's Opera Doc? -

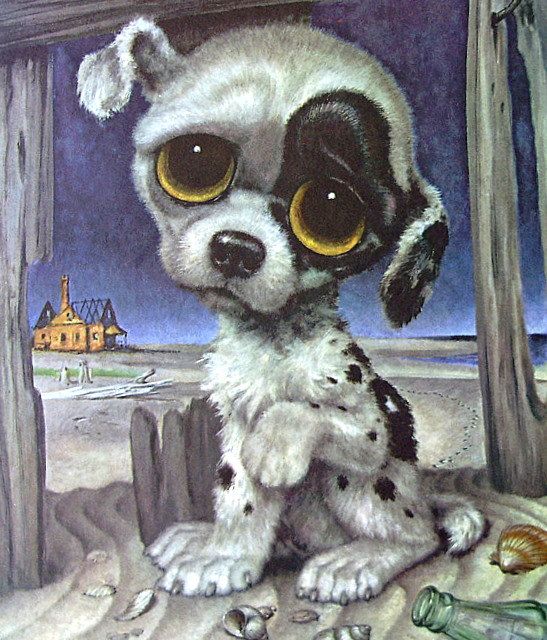

Ocular Excess

A Semiotic Morphology of Cartoon Eyes

Philip Brophy

Works referenced: Kewpie dolls, celluloid 'milk blood', OSamu Tezuka, Margaret & Walter Keane, Basil Wolverton, Ed Roth

Works referenced: Kewpie dolls, celluloid 'milk blood', OSamu Tezuka, Margaret & Walter Keane, Basil Wolverton, Ed Roth -

Japanese TV Animation in the Early Years

Animation & Animated Humans

Manabu Yuasa

Titles referenced: Astro Boy, Gigantor, The Phantom Detective, 8 Man, Wolf Boy Ken

Titles referenced: Astro Boy, Gigantor, The Phantom Detective, 8 Man, Wolf Boy Ken -

Blue-Haired Girls With Eyes So Deep You Could Fall Into Them

The Success of the Heroine in Japanese Animation

Rosemary Dean

Titles & works referenced: Sailor Moon, Nausica in the Valley of the Wind, The Laughing Target, Towards the Terra, the Takarazuka Review

Titles & works referenced: Sailor Moon, Nausica in the Valley of the Wind, The Laughing Target, Towards the Terra, the Takarazuka Review -

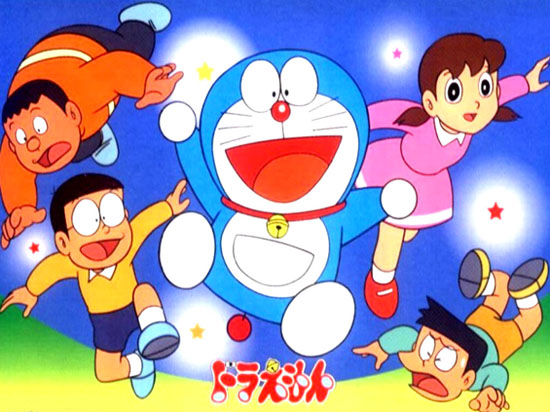

A Look Inside Doraemon's Pouch

Mark Shilling

Works referenced: Doraemon TV series, 15 Doraemon movies

Works referenced: Doraemon TV series, 15 Doraemon movies

Catalogue introduction

Animation is the most 'other-worldly' of the motion arts and has consistently proved capable of passing audiences into another dimension, be it through grotesque fantasy or simply via stylized motion effects. Kaboom is a high-key audio-visual exposure to this dimensional wonder of animation. It immerses the participant into the crazy logic, askew physics and abrasive stylistics which characterize animation as a medium with limiting formal qualities (its illustrative, graphic feel), yet one capable of stretching one's visual experience and aural sensations to unbelievable lengths.

While some streams of animation have employed complexly crafted techniques like stop-motion animation, rotoscopography and layerings of photos, collages and paintings, it is in cel animation (the inking of sequenced drawings onto sheets of plastic) that animation achieves its most brutish yet most dynamic status. And while many short animations of the non-cel variety have received critical acclaim in film festivals around the world, cel animation is the preferred medium of virtually all forms of popular modern animation. Kaboom seeks to redress a critical balance by spotlighting the overlooked artistry evident in some of the modern extremes achieved within mainstream animation.

In order to contextualize these extreme manifestations of the medium, Kaboom adopts a dual historical perspective. The exhibition is (i) chronologically sited just after the apocalyptic closure of WWII, and (ii) laterally fixed on the transcultural ties which have developed between the two domineering postwar cultures of America and Japan. In this sense, the title "Kaboom" refers to both the childlike innocence that revels in cartoonish explosions, and the ominous yet captivating aftermath of nuclear devastation which signpost the postwar sensibilities that have governed the modern and postmodern strands of the medium.

Post-WWII, all forms of media and entertainment were drastically altered - formally, stylistically, ideologically. In photographic cinema, we are familiar with a range of such changes, from Italian neo realism to American film noir. Animation similarly underwent dramatic change.

The first and most noticeable changes occurred in America with the fractured absurdism and rat-a-tat gags which genetically altered the Warner Bros. cartoon shorts, transforming them from free-wheeling joke-fests into overpowering documents of a society driven by mania, hysteria and adrenalin. The postwar Warner Bros. shorts - as is now widely accepted - were not simply `crazy': they were psychotic ideograms predicated on speed, violence and noise. It would not be until the 80s that cinema would openly immerse itself in these elements with teen movies, horror flicks, action spectacles and anarchic comedies.

The effects of American imperialization on Japanese animation are as complex as the transcultural flows which define the fabric of postwar Japan: neither can be explained in terms of immediate consequences and linear causes. As is well noted, Japan is a confounding mix of the old and the new, fluidly redefining our concept of `ritual'. In Japan, the old can be very new, and the new can be very old. Postwar Japanese animation - typified best by Tezuka's work - initially looked very old while being very new in its focus on mystical concepts of technological reincarnation and post-nuclear states of being. The influence of Disney was noticeable, yet the philosophical slants taken in numerous TV series and animated features existed in a universe far removed from the quaint domesticity of Mickey, Minnie and Pluto.

Bending slightly to the obvious restrictions inherent in trying to cover such a large terrain, Kaboom curatorially focuses on some of the key artists who have contributed much to the modern and contemporary pools of popular cel animation in America and Japan. America is represented by the careers of Bob Clampett and Ralph Bakshi, plus a selection of historically recent examples - The New Adventures Of Mighty Mouse, Ren & Stimpy, and Beavis & Butt-Head. Japan is represented by the careers of Osamu Tezuka and Hayao Miyazaki, plus a selection of key post-1980 works by Katsuhiro Otomo, Buichi Terasawa, Rumiko Takahashi, Masamune Shirow and Kenichi Sonada.

Even a sampling of work from the artists mentioned above should afford the viewer/listener an idea of the scope that has existed and still exists, hidden in the crazy-paving which maps out the animation industries in America and Japan. All the material exhibited in Kaboom is evidence of the idiosyncratic visions of those animation artists who clutched the medium as a volatile and expansive form of communication and entertainment. Enter the beautifully hideous worlds they create, reflect and explode.

Profiles

American Artists

-

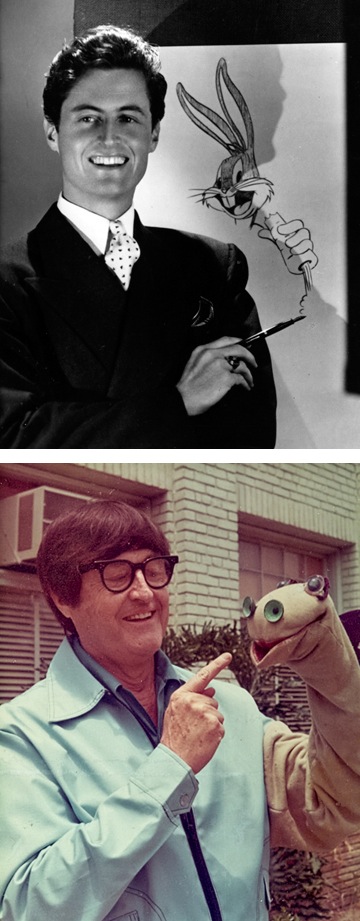

Bob Clampett

Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Beany & Cecil

As befits many creative work teams, a certain air of insanity provides the right atmospheric conditions for a group of talented individuals to pool their resources and infect each other's already crazed visions. The 'termite terrace' hive of animated activity on the Warner Brothers studios lot was one such asylum. The names of its inmates and interns are now famous: Tex Avery, Chuck Jones, Robert McKimson, Fritz Freleng, Bob Clampett. The wonderful thing about the Warner Bros. cartoon shorts from the late 30s through to the late 50s is that the more you watch them, the less generic and formulaic they become. Despite the shared characters, the re-worked gags, the staged routines and the timely media references, one can discern differing animation styles and directorial flair. While Tex Avery's eye-popping grotesqueries and their demented sexuality is clear, and Chuck Jones' sophisticated mix of human characterization and emotional inflection is evident, the work of Bob Clampett is slightly harder to define and summarize. Yet, a peculiar .... well, wackiness is consistent in just about everything he directed and produced.

As befits many creative work teams, a certain air of insanity provides the right atmospheric conditions for a group of talented individuals to pool their resources and infect each other's already crazed visions. The 'termite terrace' hive of animated activity on the Warner Brothers studios lot was one such asylum. The names of its inmates and interns are now famous: Tex Avery, Chuck Jones, Robert McKimson, Fritz Freleng, Bob Clampett. The wonderful thing about the Warner Bros. cartoon shorts from the late 30s through to the late 50s is that the more you watch them, the less generic and formulaic they become. Despite the shared characters, the re-worked gags, the staged routines and the timely media references, one can discern differing animation styles and directorial flair. While Tex Avery's eye-popping grotesqueries and their demented sexuality is clear, and Chuck Jones' sophisticated mix of human characterization and emotional inflection is evident, the work of Bob Clampett is slightly harder to define and summarize. Yet, a peculiar .... well, wackiness is consistent in just about everything he directed and produced.During his supervisor/director period at Warner Bros. (1937-1946) Clampett utilized traits from all the other directors, writers and gagmen at Warner Bros., but he pumped up the wack-o-meter further than anyone else. More importantly, he defined a certain logic of wackiness, in much the same way that Jones rewrote the laws of gravity. A typical Clampett short will contain a para-musical denouement, where a series of gags are strung together, solidly seamed with absurdist and nonsensical segues. These segues ranged from close-ups to labels bearing puns, audience signs held up by characters, cameo appearances by mutated versions of recognizable icons, and so on. Sometimes these throwaway spot gags would cascade into each other (The Great Piggy Bank Robbery, Draftee Daffy and Coal Black & de Sebben Dwarfs); other times they would appear abruptly and in a brutish manner (Bacall To Arms, Baby Bottleneck and Falling Hare). Whatever the structure of sequenced gags, Clampett's shorts for Warner Bros. were driven by a mania for cracking jokes. Cartoons like Book Revue and The Old Grey Hare almost collapse in on themselves due to the demented tone in which the gags are delivered. This distinctive dementia might have evaporated into Warner Bros history if it were not for the clarity and precision with which these Clampett-traits appeared in the TV series Beany & Cecil almost twenty years later. After Clampett left the Warner lot, he devised Time For Beany as a live puppet show for the new medium of television. Certainly a radical move for as skilled an animator-director as Clampett was, the boldness of his career decision was made more so by his retainment of character copyright and the conditions of their production. A strong vision and a keen business savvy kept Time For Beany running on American TV from 1949 into the late 50s. Returning to the animated medium, the Beany & Cecil cartoon series debuted in 1964 and received worldwide syndication by the end of the 60s.

To be frankly critical, Beany & Cecil is everything that Tiny Toons isn't: hip, smart and flip. Whereas Tiny Toons is well-aware of its cartoon-gag legacy, its scripts are often weighted by a desperate desire to let us know how hip they are. Beany & Cecil is quite the opposite, as its scenarios are not only organically wacky and astutely modulated by the character of Beany, but they are also not afraid to crack a sick joke. Like the Clampett shorts from the early 40s, there is a resolute momentum in the manic meandering of the Beany & Cecil narratives. Looking at these cartoons now, they stand up remarkably well - especially the infamous Wild Man From Wildsville which rewrites Clampett's own Porky In Wackyland to a cheesy beatnik beat; the subtle yet scathing swipe at Disneyland imperialization in Beanyland; and the carefully attenuated sarcasm aimed at corporate sponsorship in Mad-Addison Avenue. While Beany & Cecil has not endured in the Australian TV psyche as permanently as the latter Warner Bros. shorts, from the late 60s to the early 70s, it was a big hit with kids of the time. And just like early Mad magazine and the work of Gaines, Feldman, Kurztman, Martin, Davis et al have slowly been acknowledged as successfully warping many fertile imaginations, so too can Beany & Cecil and the work of Bob Clampett be viewed now as contributing to the prime definition of a term we now take for granted: wacky.

-

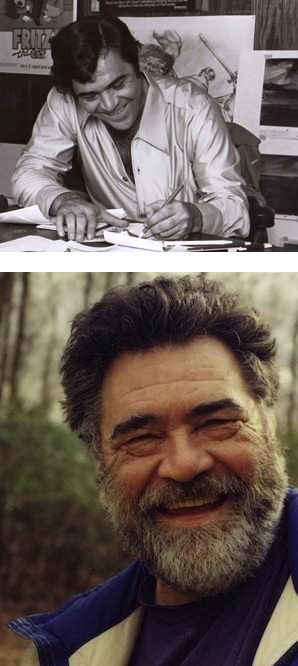

Ralph Bakshi

Heavy Traffic, Coonskin, New Adventures of Mighty Mouse, Cool World

Ten years after Beany & Cecil appeared on TV, Ralph Bakshi's first feature was released - Fritz The Cat (1971). Based on Robert Crumb's renowned underground comix hero of the same name, Bakshi's film jettisoned the world of cute furry animal characters into the harsh social conflicts symptomatic of late 60s America. While at the time it would have been hard to imagine Warner Bros. patriotic wartime cartoon bombast being on a like plane to the zippy aspirations of Fritz and his underground ilk, one can now discern a `contra-Disney' sensibility underscoring both bodies of work. Like the key animator-directors of the Warner Bros. gang, Bakshi had a clear vision of what he wanted to say and how he wanted to use the animated medium as his means of expression. Yet Bakshi's career has been as much maligned as it has been revered. While the underground 'head commix' scenes of the late 60s and early 70s rallied together to make a collective countercultural stand in publications like Zap, Bijou Funnies and Arcade, this gangly graphic bunch - like much of the counterculture - appeared to have left the cinema somewhere between Roger Corman's The Trip (1967) and Otto Preminger's Skidoo (1969). Unfettered by cross-cultural issues of audience comprehension, the head commix could 'tell it like it is'. Bakshi was the sole American animator-director of the period who tackled the complexities inherent in turning on without necessarily dropping out.

Ten years after Beany & Cecil appeared on TV, Ralph Bakshi's first feature was released - Fritz The Cat (1971). Based on Robert Crumb's renowned underground comix hero of the same name, Bakshi's film jettisoned the world of cute furry animal characters into the harsh social conflicts symptomatic of late 60s America. While at the time it would have been hard to imagine Warner Bros. patriotic wartime cartoon bombast being on a like plane to the zippy aspirations of Fritz and his underground ilk, one can now discern a `contra-Disney' sensibility underscoring both bodies of work. Like the key animator-directors of the Warner Bros. gang, Bakshi had a clear vision of what he wanted to say and how he wanted to use the animated medium as his means of expression. Yet Bakshi's career has been as much maligned as it has been revered. While the underground 'head commix' scenes of the late 60s and early 70s rallied together to make a collective countercultural stand in publications like Zap, Bijou Funnies and Arcade, this gangly graphic bunch - like much of the counterculture - appeared to have left the cinema somewhere between Roger Corman's The Trip (1967) and Otto Preminger's Skidoo (1969). Unfettered by cross-cultural issues of audience comprehension, the head commix could 'tell it like it is'. Bakshi was the sole American animator-director of the period who tackled the complexities inherent in turning on without necessarily dropping out.Crumb has little good to say about Bakshi's movie version of the Fritz The Cat comic - in fact Crumb killed off the character soon after the movie was released. But Bakshi's Fritz The Cat has a distinctive diaristic tone which is as much Bakshi's as it is Crumb's. Backing this up is Bakshi's next semi-autobiographical feature, Heavy Traffic (1973). Taking the personal enlightenment rambling of Fritz The Cat and combining them with a stark poetic view of street life (very closely modelled on Hubert Selby Jr.'s Last Exit To Brooklyn), Heavy Traffic contains moments of insight which are rare in American live action cinema of the time, let alone animation. Particularly noticeable are the connections Bakshi draws between a variety of ethnically and racially disenfranchised underclasses and how they eat into each other's very existence - a social theme which appears more forcefully in blaxploitation cinema of the time than any mainstream productions. Bakshi battled on with this theme in two successive films - the ill-fated Coonskin (1975, retitled for a later video release as Street Fight) and the maligned Hey Good Lookin' (originally 1975, but extensively reworked for a 1982 release). Both these films look at urban crime syndicates, from semi-organized Harlem operations to flaky juvenile gangs, with the message of 'underdogs-screw-underdogs' coming through loud and clear. Put these four films together and you have a sometimes strained yet consistently committed view of ghetto life and its effects on its likeable but desperate denizens.

After a commercially viable yet somewhat disappointing sidetrack into ponderous fantasy films like Wizards (1977), Lord Of The Rings (1979) and Fire & Ice (1983), Bakshi turned full circle to stylistically echo the Warner Bros. gang and sardonically rework the prewar idyllicism of Mighty Mouse - an ultra-cute, squeaky-voiced super mouse. Taking a leaf from the pages of Beany & Cecil and large doses of the Warner's multiple layers of self-referencing, Bakshi devised and produced The New Adventures Of Mighty Mouse (1985) and injected 80s iodide shows with an unabashed craziness absent from TV cartoons since the 60s. Not surprisingly, Bakshi had come to roost in a problematic place - one where he was not likely to receive cultural kudos. However The New Adventures Of Mighty Mouse (historically notable for its episodes directed by John Kricfalusi) did make its mark as even TV critics stumbled across what was a blatant swipe at everything from fundamentalist televangelists to Reagan's drug wars and other sanitary slivers of 80s life. Bakshi returned to the cinema with Cool World (1992). Where does one start with this film? Picture Who Framed Roger Rabbit? trashed by a bunch of hippies, taken for a ride by a gaggle of MTV art directors, decimated by a gang of psychotics let out of the state hospital, and then scooped up by Paramount Studio executives. Cool World is a truly mad movie, speaking at least five voices at once, with a consistently unresolved aesthetic, but I find it a fascinating if difficult film. Far from the technically impressive yet somewhat empty slickness of Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Cool World funkily flails its tentacles all over the place. Time will tell whether a genuine perversity vibrates within this bastard child of a film (at times even Bakshi avoids any kinship with it). But time has already proven Bakshi one of the very few rambunctious auteurs of American animation.

-

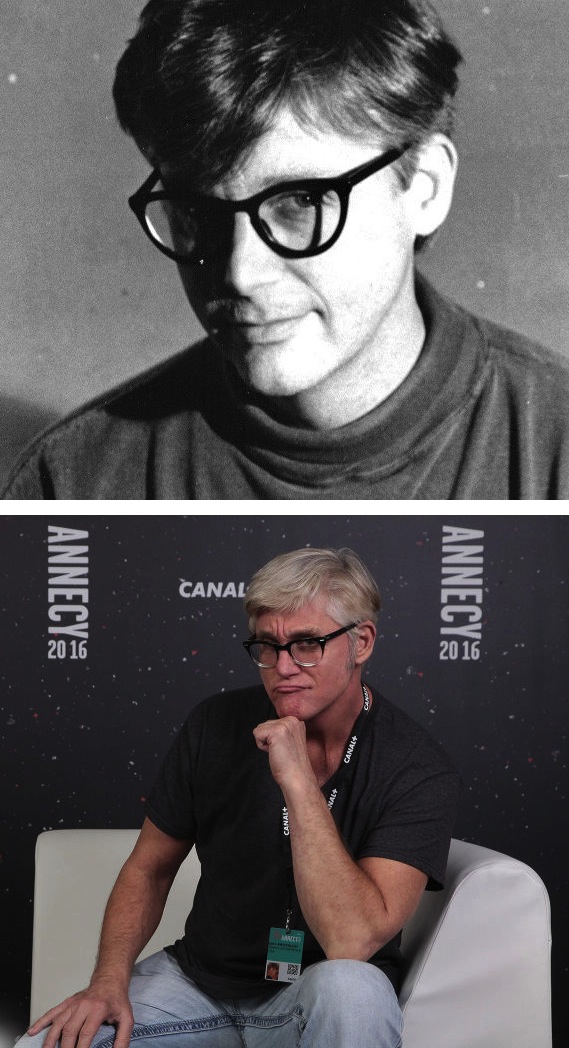

John Kricfalusi

Mighty Adventures of Mighty Mouse, Ren & Stimpy

If the 80s wasn't crazy enough in the field of kids' stuff, the 90s could end up being the worst a parent could imagine - especially if they see their kids glued to The Ren & Stimpy Show. One of the key animator-writer-directors of the Bakshi-produced The New Adventures Of Mighty Mouse, John Kricfalusi (pronounced Chris-fah-loo-see) has compacted Bob Clampett's sense of wackiness with Bakshi's neurotic edginess into a children's TV show which at times is frightening in its sophistication. I say 'sophistication' with some trepidation, as I freely apply the term even if high degrees of grossness and vulgarity are evident - as they are in the seriously repulsive antics of Ren and Stimpy. Utilizing similar production methods to those used by Bob Clampett for Beany & Cecil (storyboard sessions and director-driven projects), Kricfalusi formed Spumco at the close of the 80s to develop projects, and was shortly thereafter commissioned to do a series for MTV's subsidiary kid channel Nickelodeon. The resulting programme - The Ren & Stimpy Show (1991) - is still being produced, but Kricfalusi (the show's creator) and Spumco were unfortunately fired from the show's production. Much has been written since about the Kricfalusi/Spumco episodes and those which followed their departure, but the concept, characters and overall sensibility of The Ren & Stimpy Show largely spring from the clear and obsessive vision of Kricfalusi.

If the 80s wasn't crazy enough in the field of kids' stuff, the 90s could end up being the worst a parent could imagine - especially if they see their kids glued to The Ren & Stimpy Show. One of the key animator-writer-directors of the Bakshi-produced The New Adventures Of Mighty Mouse, John Kricfalusi (pronounced Chris-fah-loo-see) has compacted Bob Clampett's sense of wackiness with Bakshi's neurotic edginess into a children's TV show which at times is frightening in its sophistication. I say 'sophistication' with some trepidation, as I freely apply the term even if high degrees of grossness and vulgarity are evident - as they are in the seriously repulsive antics of Ren and Stimpy. Utilizing similar production methods to those used by Bob Clampett for Beany & Cecil (storyboard sessions and director-driven projects), Kricfalusi formed Spumco at the close of the 80s to develop projects, and was shortly thereafter commissioned to do a series for MTV's subsidiary kid channel Nickelodeon. The resulting programme - The Ren & Stimpy Show (1991) - is still being produced, but Kricfalusi (the show's creator) and Spumco were unfortunately fired from the show's production. Much has been written since about the Kricfalusi/Spumco episodes and those which followed their departure, but the concept, characters and overall sensibility of The Ren & Stimpy Show largely spring from the clear and obsessive vision of Kricfalusi.While the Warner Bros. (particularly Clampett and Avery) takes are easy to spot in The Ren & Stimpy Show, it is the consistent personalized perspective given the characters of Ren, Stimpy and occasional sidekicks which marks the series as visionary. The world of Ren and Stimpy - rendered in Pollock splatters, Danish modern and Wham-O packaging - is like The Twilight Zone run by The Garbage Pail Gang. Societal control looms forebodingly while Ren & Stimpy somehow manage to obliterate all codes of behaviour, taste and rationalism as they ease, tease and squeeze each other's addled minds. 'Dysfunctional' does not come close to framing the relationship between the two: like the great duos of the Warner Bros. shorts, Ren & Stimpy expose the many facets of their psychologically complex characters, leaving them always to work things out among themselves. Of course, The Ren & Stimpy Show is hilarious. Even when their visceral doodling with body parts and substances becomes overbearing, you can still laugh while wretching. But just as The Garbage Pail Gang (a series of bubble gum cards devised by Art Speigelman and Mark Newgarden for Topps) eviscerated the oppressive warmth of The Cabbage Patch Kids, so too do the seminal episodes of The Ren & Stimpy Show achingly portray a whacked-out era wherein any form of psychosis is good for a laugh. And John Kricfalusi's creation (and others he is currently developing ) is definitely psychotic and definitely funny.

-

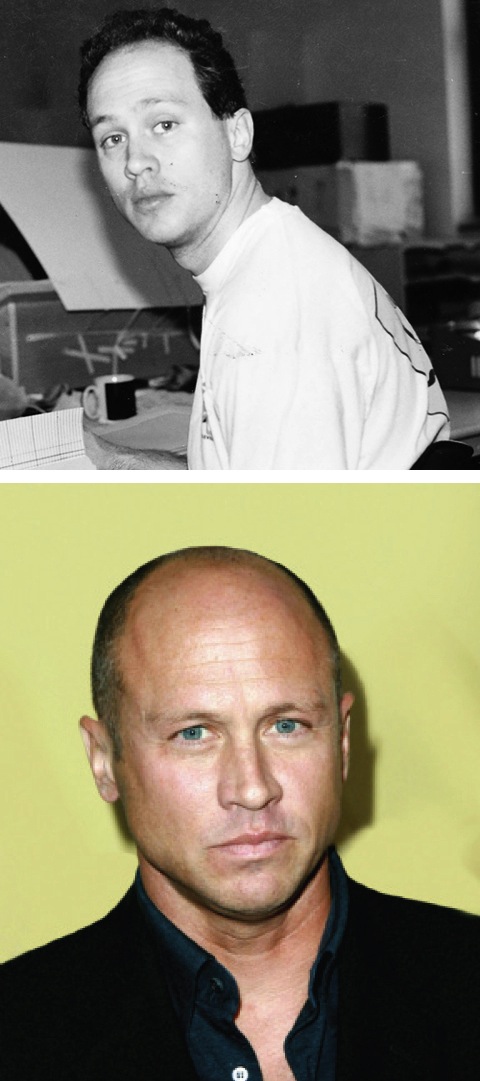

Mike Judge

Beavis & Butt-head

As yet another compendium is lodged in the special Generation X shelf in the bookstore, true empty-headedness rules in a place the intelligentsia will never govern: the mall. There you will find a race of beings cast from the same mold used to shape Beavis & Butt-Head. Bluntly portraying the so-called 'slacker' or moron culture satirized in gross-out teen comedies like Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure and Wayne's World, Beavis & Butthead are animated figures who host MTV as if they are just watching the show, and all they do is make really dumb, moronic wise-cracks which would never make it outside a boy teenager's bedroom. Just as Clampett's cartoons reflected the bent perspectives of postwar America, and Bakshi's features staked counter-cultural claims against his repressive period, Beavis & Butthead reflect America's spaced-out yet claustrophobic mall-culture. And like all challenging forms of art and entertainment, this reflection is sometimes too close to the real thing to allow an audience a safely distanced relationship with the characters and their creator, Mike Judge.

As yet another compendium is lodged in the special Generation X shelf in the bookstore, true empty-headedness rules in a place the intelligentsia will never govern: the mall. There you will find a race of beings cast from the same mold used to shape Beavis & Butt-Head. Bluntly portraying the so-called 'slacker' or moron culture satirized in gross-out teen comedies like Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure and Wayne's World, Beavis & Butthead are animated figures who host MTV as if they are just watching the show, and all they do is make really dumb, moronic wise-cracks which would never make it outside a boy teenager's bedroom. Just as Clampett's cartoons reflected the bent perspectives of postwar America, and Bakshi's features staked counter-cultural claims against his repressive period, Beavis & Butthead reflect America's spaced-out yet claustrophobic mall-culture. And like all challenging forms of art and entertainment, this reflection is sometimes too close to the real thing to allow an audience a safely distanced relationship with the characters and their creator, Mike Judge.Put plainly, Beavis and his demented pal Butt-Head are ugly: they sound ugly, they're drawn ugly, they exude ugly. But it is an ugliness that Judge seems to know instinctively. It is his guttural 'huh-huh-huh' which infects the voice-track of every episode; it is his often ad-libbed dialogue which is set to their retarded lip movements; and it is his drawing style which sets the visual aesthetic just this side of the toilet wall. I say this in praise, of course, because Judge's disarming view of a couple of losers like Beavis & Butt-Head nonetheless evokes a mix of pity and amazement in how one relates to such characters. Recalling existential teen films like Over The Edge (1979), Fast Times At Ridegmont High (1982), The Boys Next Door (aka For No Apparent Motive, 1985) and River's Edge (1986), Beavis & Butt-Head is a trip across the mindscapes of teenagers who are 'lost' yet comfortable with their detached state of being. Beavis and Butt-head will laugh at each other's trials and tribulations with extreme insensitivity, but they're also best friends. Perhaps that is why for many people, they are the perfect antidote to TV shows like The Wonder Years and thirtysomething.

Profiles

Japanese Artists

-

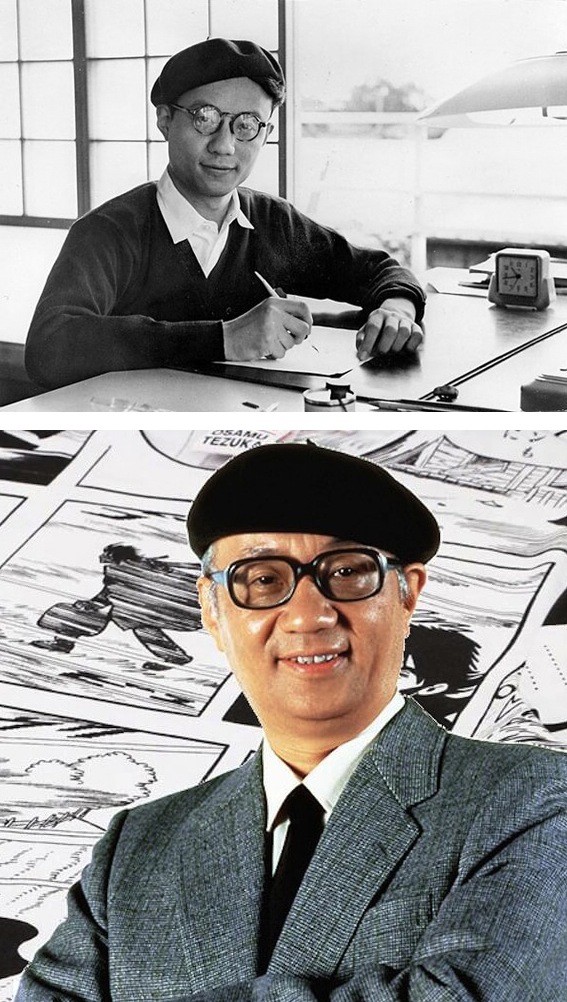

Osamu Tezuka

works

Often referred to as `Japan's Walt Disney', Osamu Tezuka is probably the single most important figure in establishing animation as a mass entertainment medium in Japan. Like many animators in Japan, Tezuka first gained notoriety and success as a manga (comic) writer and illustrator. The manga industry is the largest in the world, and the Japanese - with their uniquely non-judgemental perspective of culture - have had no problem in manga critical respect despite its mass popularity. Consequently, by the early 60s Tezuka was regarded with the kind of esteem that the west usually reserves for esteemed novelists and the like. While much of Tezuka's approach to animation can be aligned with aspects of Disney's pre-WWII work, Tezuka's work generally is quite adult in tone - often effectively incorporating elements of Shinto mysticism. His comic work established this in the 50s, and similar concerns were carried through his TV series of the 60s and many feature films. To western audiences the faces and voices of Astro Boy (1963, aka Tetsuwan Atom), Kimba the White Lion (1965-66, aka Jungle Emperor) and The Amazing 3 (1965-66, aka W3 or Wonder 3) are very familiar - even though most people are unaware that these cartoons were Japanese. And despite some heavy-handed American post-dubbing, the soulful and contemplative strains of Astro Boy (wondering who his parents were) and Kimba (accepting death as a way of life in the jungle) emanated from these imported productions.

Often referred to as `Japan's Walt Disney', Osamu Tezuka is probably the single most important figure in establishing animation as a mass entertainment medium in Japan. Like many animators in Japan, Tezuka first gained notoriety and success as a manga (comic) writer and illustrator. The manga industry is the largest in the world, and the Japanese - with their uniquely non-judgemental perspective of culture - have had no problem in manga critical respect despite its mass popularity. Consequently, by the early 60s Tezuka was regarded with the kind of esteem that the west usually reserves for esteemed novelists and the like. While much of Tezuka's approach to animation can be aligned with aspects of Disney's pre-WWII work, Tezuka's work generally is quite adult in tone - often effectively incorporating elements of Shinto mysticism. His comic work established this in the 50s, and similar concerns were carried through his TV series of the 60s and many feature films. To western audiences the faces and voices of Astro Boy (1963, aka Tetsuwan Atom), Kimba the White Lion (1965-66, aka Jungle Emperor) and The Amazing 3 (1965-66, aka W3 or Wonder 3) are very familiar - even though most people are unaware that these cartoons were Japanese. And despite some heavy-handed American post-dubbing, the soulful and contemplative strains of Astro Boy (wondering who his parents were) and Kimba (accepting death as a way of life in the jungle) emanated from these imported productions.Responsibility in advancing technology, caring for all life-forms, and a belief in microcosmic and macrocosmic cycles of reincarnation are key themes which have appeared in all of Tezuka's work, marking him a proto-new-ager living precariously in postwar Japan. Strikingly, these key themes reside with depth and clarity in his children-oriented material (like the Unico trilogy of films - Unico, 1981; Unico: To The Island Of Magic, 1983; Unico: Black Cloud & White Feather, 1989) and his more adult-oriented works (like the series of Phoenix films - Dawn, 1978; Space Firebird 2772, 1981; Karma, Yamato and Space, all 1986). And perhaps the ultimate grace of Tezuka's work is that just at the point they appear cloying and even saccharine, they subtly resonate with an uneasy mournful tone. Tezuka's career paralleled the rise of the Japanese animation industry. Inspired by Disney, he set up his own production company - Mushi Studios (1961-1973) - which became the training ground for many of the following generation of Japanese animators (including Katsuhiro Otomo and Buichi Terasawa). The Disney studios - like so many animation studios - started off as a vibrant, independent facility, but as many critics have observed, the corporate mentality of the Disney world eventually overtook the artistic direction of Walt Disney's pioneering vision. Tezuka's vision has arguably remained intact. Not only do the bulk of his animations convey a comparable style and tone to his original manga, but also his views of the future have melded comfortably into our present. Disney's recent realms of fantasy often display a desperate air of nostalgia and feel-good wishful thinking. More importantly, while Disney appeared to forgo further artistic experimentation after a unfortunate limited response to the ground-breaking Fantasia (1941), Tezuka continually returned to the personally expressive medium of the short animation, exploring a variety of techniques and ideas in early films like Memory and Mermaid (both 1964) and Pictures At An Exhibition (1966), and later films like Jumping (1984), Broken Down Film (1985) and Self Portrait (1988).

Jumping - a 6 and 1/2 minute movie which took 2 and 1/2 years to make, using over 4000 cels - best sums this up. Taken totally from the point of view of a child who is jumping on an outer-suburban street, the child's jumps get bigger and bigger. She starts jumping over fences, then trees, next houses. Suddenly she is jumping over fields, blocks of houses. She jumps out of the suburbs toward the city, each jump taking longer in the air, alighting briefly on the ground to fantastically spring to even further heights. Before long she is jumping across bays, through skyscrapers, into adjoining countries. She jumps through a war-torn field, eventually jumping dead on the spot of a huge detonation. She lands in hell; some demons pitch-fork her back through the earth's crusty layers onto the surface - back to her home street. Jumping is like a synaptic flash in Tezuka's mind, which reveals his manner of fiction wondering as well as how perfectly his vision is serviced by animation. Tezuka ventured mostly into the fields of science and speculative fiction, and his animations can bring into focus what live-action sci-fi often attempts but rarely succeeds in creating: a realm of dimensional possibilities. Tezuka's work is often devoid of all plausibility, but freed of pseudo-rational verisimilitude he can freely flow through a current which philosophy, poetry and technology co-inhabit. In Tezuka's universe, planets come and go; energies manifest themselves on multiple lanes; and machines virtually invent themselves. This specific type of fantasy functions like the uninhibited child (similar to the one in Jumping) who imagines how machines operate. Using this child-like illogical sense of wonder as a basis for his narratives and designs, Tezuka strikes at the central desire behind much technological progress and futuristic preoccupation. In doing so he reverses the established Euro centric quest for knowledge ("how can I invent a machine to do this?") with oriental contemplation ("imagine if a machine could do this!").

-

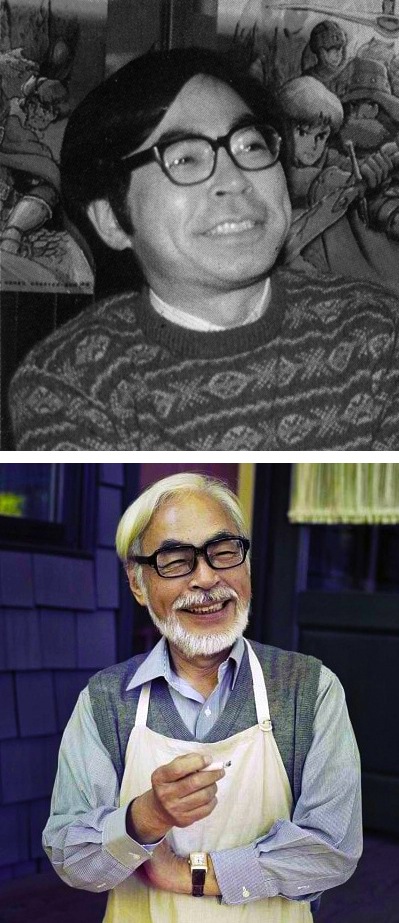

Hayao Miyazaki

Nausica of the Valley of the Wind, Tottoro, Kikki's Delivery Service, Laputa

Hayao Miyazaki is among the best known of the postwar generation of animators who started out at either Tezuka's Mushi studios or the large Toei animation company. Ostensibly a manga writer-artist with many publications to his credit (Nausica: Valley Of The Wind being his best known), he has often worked in tandem with another animator-director Isao Takahata who has produced some of Miyazaki's films. Miyazaki in turn produced Takahata's Only Yesterday (aka Falling Tears Of Yesterday, 1991) and Heisei Tanuki War PonPoko (1994). Each animator-director has their own graphic style, mode of characterization and directorial preoccupations, and obviously their working relationship aids in each achieving his artistic intentions. While Takahata's work is highly naturalistic and usually contemporaneous, Miyazaki's subjects (often thinly-veiled socio-political allegories) are set in bizarre mish-mashes of worlds plucked from European history books. Nonetheless Miyazaki's films are uniquely Japanese in their eclectic approach to stylistic conglomeration. As such, he opens up even further the dimensional possibilities of how the animated feature can engage an audience in an emotionally charged yet seriously contemplative work of fiction.

Hayao Miyazaki is among the best known of the postwar generation of animators who started out at either Tezuka's Mushi studios or the large Toei animation company. Ostensibly a manga writer-artist with many publications to his credit (Nausica: Valley Of The Wind being his best known), he has often worked in tandem with another animator-director Isao Takahata who has produced some of Miyazaki's films. Miyazaki in turn produced Takahata's Only Yesterday (aka Falling Tears Of Yesterday, 1991) and Heisei Tanuki War PonPoko (1994). Each animator-director has their own graphic style, mode of characterization and directorial preoccupations, and obviously their working relationship aids in each achieving his artistic intentions. While Takahata's work is highly naturalistic and usually contemporaneous, Miyazaki's subjects (often thinly-veiled socio-political allegories) are set in bizarre mish-mashes of worlds plucked from European history books. Nonetheless Miyazaki's films are uniquely Japanese in their eclectic approach to stylistic conglomeration. As such, he opens up even further the dimensional possibilities of how the animated feature can engage an audience in an emotionally charged yet seriously contemplative work of fiction.Miyazaki's central characters have almost exclusively been children or teenagers, and often girls. While this is the case with much Japanese animation - be it aimed at children or not - Miyazaki's characters behave astutely and with an assured maturity. I once heard someone (in a shopping mall) say that Lisa in The Simpsons is unrealistic, because a girl her age wouldn't be so aware. The eponymous character of Nausica (1983) is not unlike Lisa, except that Nausica is allowed - through Miyazaki's symbolic expression, at least - to play the role of heroine, tactician and arbitrator in a territorial feud between warring clans. American animation finds it difficult enough to allow Lisa to momentarily halt the petty squabbling of Bart and Homer fighting over the breakfast bacon. The figure of a sensitive yet strong-willed female teen recurs in Kikki's Delivery Service (1989) - a story of a young witch at the point of reaching puberty, sent from her home to work with and learn about humans. Both Nausica and Kiki's Delivery Service's style of animation is considerably removed from the preceding decade of robot-fixated scenarios (from Go Nagai's seminal Mazinger and Grandizer series through to Yoshiyuki Tomino's influential MS Gundam series), not only because of their transformation from gleaming high-tech space settings into an organic 'old worlds' of elemental invention, but also due to their distinctive pacing and attention to minor detail. This is clear in the luscious and lingering forest scenes of Nausica and the languid moving of billowing clouds in Kiki's Delivery Service. Miyazaki's films are not just about contemplative figures and moments: the films themselves induce contemplative states, often by phantasmagorically transporting the viewer/listener into the mood, mind and memory of a character. Centred on some remarkably realistic dynamic movement, Miyazaki's work can shift with ease from these still passages to giddy and vertiginous sequences. The many chases scenes in Laputa (1986) have often been cited as simulating live action footage depicting similar momentum, while the sensation of flight features in this film as well as Nausica, Kiki's Delivery Service and Porco Rosso (1992). Perhaps what typifies Miyazaki as a director working beyond the 70s epoch of Japanese animation and its frenetic combinations of 2001: A Space Odyssey musings, Star Wars action and Bandai toys is how he figures apocalyptic symbolism within his earthbound and earthy narratives.

The best example of this occurs in My Neighbor Totoro (1988). After the children have discovered the existence of a magical spirit-being in the rural garden of their new country house, Totoro performs a fun ritual which demonstrates his powers. By willing hard, he directs some freshly planted seeds to grow. Building up energy, he conjures the fledgling shafts into a towering tree which bursts out of the ground in an orgasmic rush of lush vegetation. Frighteningly, the image of the tree looks identical to the infamous 'mushroom cloud' of an atomic detonation - and the excited children giggle with glee. This image in Totoro is simultaneously breath-taking, heart-warming and haunting. In Laputa, an apocalyptic ending erupts after a character removes a secret crystal from a wall in a central chamber, causing a huge sky castle made of earth and rock to then disintegrate like a clay model from the set of a 50s Godzilla movie. Once again, the frailty of an ecology is posed locally (Japan being accustomed to earthquakes) and globally (the sky castle being a succinct symbol of the earth). In a sense, Miyazaki rewrites Tezuka by updating the sensibilities of his subjects and characters (effectively draining them of any Disney-esque inflection) without loosing the central issues of a peculiarly Japanese post-nuclear mode of imagining other worlds. If Tezuka is nostalgic, Miyazaki is elegiac - painting worlds which ideally might exist - the agricultural utopia of Nausica; the small town charm of Kiki's Delivery Service; the second lease of life in the country of Totoro - but which we nonetheless have to face may only exist on painted cels.

-

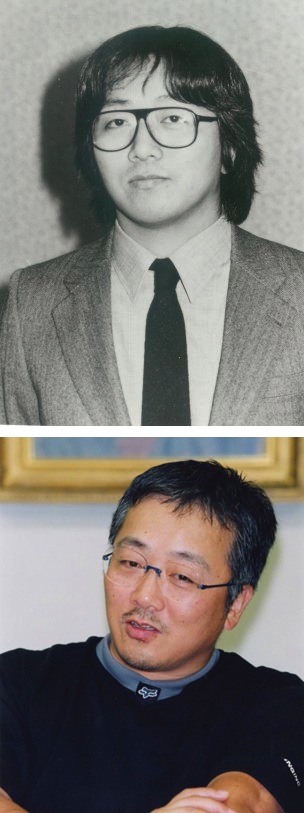

Katsuhiro Otomo

Akira

Katsuhiro Otomo's Akira (1987) has been the flagship heralding the era of 90s cyberpunk animation. As an animation, it directly drew upon an image of Japan refracted through western eyes - namely, Ridley Scott's Bladerunner (1982). In an indirect way, the global cult success of that film legitimized the post-nuclear idiosyncrasies of Japan to a younger generation to whom the modern world had no overt connections to the Japan's postwar trauma. In the countless cyberpunk animations since Bladerunner, nuclear detonation is a given; technology is a workable means to limitless ends; and the apocalypse is just around the corner. Akira opens with a sequence that condenses many primary elements that qualify a peculiar Japanese fix on the apocalypse. After a flash appears on the horizon's edge, a huge ball of black energy grows and expands its circumference in sheets of white fallout, gravitating silently toward our location and engulfing the screen in silent white. We are made - by virtue of our point-of-view - to experience that blast. In a perverse 'you-are-there' effect, we are made not to witness destruction, but to be symbolically destroyed. American movies tend to allow us the privileged position of seeing & hearing destruction; rarely do they figuratively 'destroy us'.

Katsuhiro Otomo's Akira (1987) has been the flagship heralding the era of 90s cyberpunk animation. As an animation, it directly drew upon an image of Japan refracted through western eyes - namely, Ridley Scott's Bladerunner (1982). In an indirect way, the global cult success of that film legitimized the post-nuclear idiosyncrasies of Japan to a younger generation to whom the modern world had no overt connections to the Japan's postwar trauma. In the countless cyberpunk animations since Bladerunner, nuclear detonation is a given; technology is a workable means to limitless ends; and the apocalypse is just around the corner. Akira opens with a sequence that condenses many primary elements that qualify a peculiar Japanese fix on the apocalypse. After a flash appears on the horizon's edge, a huge ball of black energy grows and expands its circumference in sheets of white fallout, gravitating silently toward our location and engulfing the screen in silent white. We are made - by virtue of our point-of-view - to experience that blast. In a perverse 'you-are-there' effect, we are made not to witness destruction, but to be symbolically destroyed. American movies tend to allow us the privileged position of seeing & hearing destruction; rarely do they figuratively 'destroy us'.This possibly explains why so many Japanese animations - from Astroboy through to Akira and beyond - depict huge bomb explosions by dislocating the sound from the image. As in the opening Akira blast (and other times throughout the film) these explosions tend to occur in silence - suggesting that at the point of death we might not be able to hear the actual explosion, or at least live to tell it as a memory. In this deathly silence we exist only as ghostly viewers. This is confirmed by the proceeding images of the monstrous gaping crater left after the bomb drop which created Neo-Tokyo: a post-apocalyptic womb. In another sense, we have been reborn through this perspective. As viewers, we are now emerging from that womb, having died in the white blast, now living as post-nuclear viewers in the black hole. When a bomb is dropped on a nation, it causes not only a convex/concave effect upon the landscape (like the white-ball/black-hole of Akira and even earlier manga work of Otomo's); it scars the national psyche in an analogous way. The presence and reverberation of the bomb is always somehow retained. In this manner the image of an explosion & its aftermath (balls of energy giving way to holes) are used persistently in Japanese animation. Otomo appears to be one of the key manga artists of the 80s who utilized impressive graphic skill to illustrate in a spectacular way the many fissures and fractures which underscore Japan's maniacal affluence.

Though I have talked much about Akira here, the themes, ideas and images mentioned above have been rendered visible in much of Otomo's work since 1983: from his pioneering illustrations to his CMs (commercial advertisements for TV: Suntory, Canon and Honda) to his manga (Roujin Z, Domo, The Legend Of Sister Sarah) to his film work. Being the stylistic and technical tour de force it is, Akira understandably took up much of Otomo's time and energy, so feature films have been few - hence his short contributions to the anthology films Manie-Manie (1986), Robot Carnival (1987) and Neo-Tokyo (1989). But clearly a proponent of quality over quantity, Otomo's overtly politicized post-apocalyptic view of contemporary Japan and the complex social infrastructure of its traumatized citizens and fringe dwellers quite likely delivers a critique that contemporary Japanese cinema has had difficulty in formulating with as much potency as Otomo.

-

Masamune Shirow

Appleseed, Black Magic M-66, Ghost In The Shell

Based in Osaka and a contemporary of Otomo, Masamune Shirow is one of the group of manga artists whose dramatic works are shaped by critical perspectives on contemporary Japan. Even though both Otomo and Shirow project their views onto future scenarios (and Miyazaki onto historical imaginings), their readings of current Japan is legible. Shirow is particularly concerned with the relationships between crime proliferation, law enforcement and military engagement, and how those relationships impact on both criminals and law enforcers. Shirow's best known work Dominion: Tank Police (manga 1986; AOV 1989) covers a lot of ground in this respect, initially setting up a farcical relationship between the amoral adrenalin-pumped criminals (Buaku, Unipuma and Annapuma) and the Tank Police (a motley crew somewhere between Police Academy and Hill Street Blues). This is then diffused by a focal tie between one member of each - Buaku and the female rookie cop, Leona. And before you can figure where the story is going, a whole side of Buaku is revealed: he is actually a genetically engineered droid searching for the origins of his birth - an existential theme which echoes Astro Boy.

Based in Osaka and a contemporary of Otomo, Masamune Shirow is one of the group of manga artists whose dramatic works are shaped by critical perspectives on contemporary Japan. Even though both Otomo and Shirow project their views onto future scenarios (and Miyazaki onto historical imaginings), their readings of current Japan is legible. Shirow is particularly concerned with the relationships between crime proliferation, law enforcement and military engagement, and how those relationships impact on both criminals and law enforcers. Shirow's best known work Dominion: Tank Police (manga 1986; AOV 1989) covers a lot of ground in this respect, initially setting up a farcical relationship between the amoral adrenalin-pumped criminals (Buaku, Unipuma and Annapuma) and the Tank Police (a motley crew somewhere between Police Academy and Hill Street Blues). This is then diffused by a focal tie between one member of each - Buaku and the female rookie cop, Leona. And before you can figure where the story is going, a whole side of Buaku is revealed: he is actually a genetically engineered droid searching for the origins of his birth - an existential theme which echoes Astro Boy.These kind of knots, twists and turns appear in Shirow's Appleseed (manga 1988; film 1990?). More a serious exploration of cyborgian ethics and corporate corruption (particularly in the animated version), Appleseed features a unique mecha design aesthetic which rode the wave of late 80s organic design which is still visible in many aspects of Japanese architecture and industrial design. This style of bulbous forms, globular shafts and crustaceous shells is partially inspired by the design of H.R. Geiger and Moebius, but Shirow's slant on them is all his own. The title mecha of Black Magic: Mario M-66 (manga?; AOV 1987) crystalizes Shirow's slant on the curvaceously metallic, giving us a totally post-nuclear oriental reformulation of the European modernist aesthetic which shaped the body of the robotic Maria in Metropolis over 50 years earlier. Predominantly a tense runaway-cyborg suspense story, Black Magic: Mario M-66 displays its critical purpose through a suspenseful triangle between the androgynous M-66, Sybel - an equally macho-feminine location news camera person - and the ridiculously cute Felice whom the M-66 is hell-bent on destroying. The scene where all three are trapped in an elevator theatricalizes this unique battle between the sexual machines. One of Shirow's recent works Ghost In The Shell (manga 1989; animation 1994) takes all these ideas, themes and styles and blends them with para-mystical notions of how the elite SHELL security police - part human but comprised mostly of cybernetic implants - have developed a paranormal consciousness. This particular blend characterizes the more contemporary aspects of Japanese animation: its weaving of mysticism; its view of technology; its concept of energy; and its diffusion and redistribution of sexual differences.

-

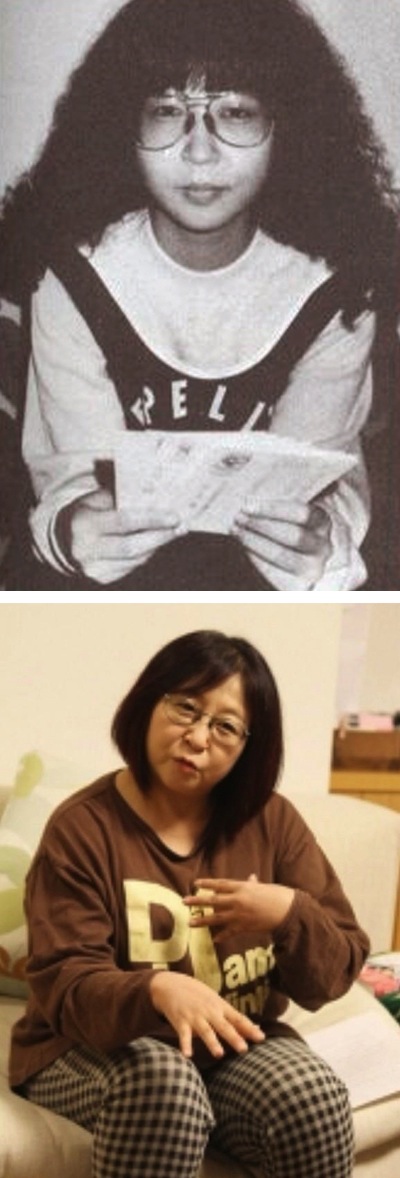

Rumiko Takahashi

Urusei Yatsura, Ranma 1/2, Mermaid Forest

Typifying much of the 'crazy' sensibilities which arose in both Japanese new wave cinema and numerous manga in the early 80s, Rumiko Takahashi has come to crystallize the wild and free-form mutant sitcom style of comedy that for the west sums up 'those wacky Japanese'. But what makes Takahashi all the more interesting is that while most manga artists become identities by developing clear stylistic traits within select genres, Takahashi stands out by virtue of the broad range of tones & styles in her work. Urusei Yatsura (often loosely translated as Those Obnoxious Aliens, commencing 1978) & Ranma 1/2 (commencing 1982) are the most famous of her anarchic comedies. Both are still being produced today, as manga, TV series and feature animations. Located in a high school, Urusei Yatsura follows the exploits of the nerdy Moroboshi who is befriended by Lum - an innocent but wild alien wearing high boots and a leopard skin bikini. She is part guardian angel, part true love but mostly the cause of his daily tribulations. Ranma 1/2 is truly weird, being about young Ranma who changes sex when splashed with cold water. The only way to change back to is by being splashed with hot water. His father suffers a similar fate, except instead of changing sex he turns into a giant panda. They live at his uncle's place - a widower who runs a martial arts school with three daughters: a tomboy (Akane), a 'good' girl (Kasumi) & a very cynical girl (Nabiki).

Typifying much of the 'crazy' sensibilities which arose in both Japanese new wave cinema and numerous manga in the early 80s, Rumiko Takahashi has come to crystallize the wild and free-form mutant sitcom style of comedy that for the west sums up 'those wacky Japanese'. But what makes Takahashi all the more interesting is that while most manga artists become identities by developing clear stylistic traits within select genres, Takahashi stands out by virtue of the broad range of tones & styles in her work. Urusei Yatsura (often loosely translated as Those Obnoxious Aliens, commencing 1978) & Ranma 1/2 (commencing 1982) are the most famous of her anarchic comedies. Both are still being produced today, as manga, TV series and feature animations. Located in a high school, Urusei Yatsura follows the exploits of the nerdy Moroboshi who is befriended by Lum - an innocent but wild alien wearing high boots and a leopard skin bikini. She is part guardian angel, part true love but mostly the cause of his daily tribulations. Ranma 1/2 is truly weird, being about young Ranma who changes sex when splashed with cold water. The only way to change back to is by being splashed with hot water. His father suffers a similar fate, except instead of changing sex he turns into a giant panda. They live at his uncle's place - a widower who runs a martial arts school with three daughters: a tomboy (Akane), a 'good' girl (Kasumi) & a very cynical girl (Nabiki).Maison Ikkoku (1985) was an earlier manga series made into a limited TV series. Not as infamous as her comedies, Maison Ikkoku - a soap opera about the tenants in a small rooming house run by a beautiful widow - is a skilled low-key melodrama. Its attention to detail (milk circling in a cup of coffee; summer cicadas; trains passing in the distance; a leaf falling from a tree) displays an affinity with the more sombre rhythms of Haiku poetry and even the cinema of Ozu. In general, Takahashi's work appeals to a cross-gendered audience while being stylistically and thematically rooted in the shonen genres (girls and women's manga). While teen sex hang-ups and sexual differences are hysterically expounded throughout Urusei Yatsura and Ranma 1/2, that same sense of difference is handled in complex psycho-sexual ways in Mermaid Forest (1990?) where themes of incest, bestiality & cannibalism figure prominently. Mermaid Forest is part of a series of one-off stories Takahashi did under the title series Rumik World (manga - 198?; animation 199?). The Mermaid Forest story makes up two parts of this series (the second part titled Mermaid's Scar), and is based on island folklore concerning the belief that if you eat the flesh of a mermaid you will become immortal. Both stories are centred on young Yuta and the younger Mana who are essentially teenagers slowly coming to the realisation of the burden of forever remaining young. The main drama in the first story revolves around twin sisters Towa and Sawa, one of whom gave the other mermaid flesh to recover from a terminal illness. The sick sister lives, but only through her unrequited lover (now an impotent old doctor) sawing off arms from fresh morgue bodies to replace her monstrously contaminated arm. Cited as one of the most popular manga artists currently working in Japan, Takahashi is a powerful example of the dense and multi-layering of themes, symbols and icons which can comprise contemporary Japanese animation.

-

Kenichi Sonada

Bubblegum Crisis/Crash, Gall Force, Gunsmith Cats

Just as the Overfiend series throws some sharp curves on issues of power & its visual/symbolic representation, Bubblegum Crisis/Crash (1987/92) and the Gall Force series (since 1986) do likewise - but by foregrounding aspects of gender in their depiction of power. Both these latter series are based extensively on the distinctive chara designs (characters) of Kenichi Sonada. Full of curvaceous women in mind-boggling hi-tech body-suit armory, Sonada's designs form the archetypal iconography which appeals to the otaku (nerdy fanboy) market which keeps a large proportion of the Japanese manga and anime industries buoyant. Yet despite the outrageous puerility which drives Sonada's work, they give rise to interesting twists when viewed from a western perspective.

Images of women in western audio-visual fiction generally receive little exposure, promotion & celebration when compared to the innumerable images of men consistently used as neutral vessels for depicting control, valour, foresight & success. Since the early 80s animation explosion in Japan, Japanese animation has produced a remarkably low proportion of male hero images & scenarios. In fact the bulk of all futuristic scenarios are centred on female protagonists or all-women groups & societies. The OVA series of Bubblegum Crisis (1987) and Bubblegum Crash (1991) and the Gall Force occasional series of OVAs and films (Eternal Story, 1986; Destruction, 1987; Stardust War, 1988; and Rhea Gall Force, 1992) are indicative of these all-women domains, wherein women have no fear of technology; are capable in extreme and threatening situations; collectively work to deal with situations; and actively dismiss the mock-heroism of their male counterparts (if indeed they even appear in the film). While this would be an oddity in western entertainment, in Japanese animation it is an established code.

Just as the Overfiend series throws some sharp curves on issues of power & its visual/symbolic representation, Bubblegum Crisis/Crash (1987/92) and the Gall Force series (since 1986) do likewise - but by foregrounding aspects of gender in their depiction of power. Both these latter series are based extensively on the distinctive chara designs (characters) of Kenichi Sonada. Full of curvaceous women in mind-boggling hi-tech body-suit armory, Sonada's designs form the archetypal iconography which appeals to the otaku (nerdy fanboy) market which keeps a large proportion of the Japanese manga and anime industries buoyant. Yet despite the outrageous puerility which drives Sonada's work, they give rise to interesting twists when viewed from a western perspective.

Images of women in western audio-visual fiction generally receive little exposure, promotion & celebration when compared to the innumerable images of men consistently used as neutral vessels for depicting control, valour, foresight & success. Since the early 80s animation explosion in Japan, Japanese animation has produced a remarkably low proportion of male hero images & scenarios. In fact the bulk of all futuristic scenarios are centred on female protagonists or all-women groups & societies. The OVA series of Bubblegum Crisis (1987) and Bubblegum Crash (1991) and the Gall Force occasional series of OVAs and films (Eternal Story, 1986; Destruction, 1987; Stardust War, 1988; and Rhea Gall Force, 1992) are indicative of these all-women domains, wherein women have no fear of technology; are capable in extreme and threatening situations; collectively work to deal with situations; and actively dismiss the mock-heroism of their male counterparts (if indeed they even appear in the film). While this would be an oddity in western entertainment, in Japanese animation it is an established code.

Bubblegum Crisis and Bubblegum Crash feature the immensely popular characters Celia, Priss, Linna and Nene who form the Knight Sabers - a vigilante group of mercenaries in Mega Tokyo, 2032. On the one hand this is not far removed from the American tacky-wacky of Josie & The Pussycats and Charlie's Angels, but the psychological differences between the characters in the Bubblegum series makes it extremely involving. Gall Force is centred on the power struggle between genders. Two interplanetary species - the Paranoids (who look like human women) & Zoenoids (who look like slimy biomorphs with guttural male voices) - have warred for eons. A universal council decides that the only way for the war to end is through genetically cross-fertilizing both species, to create a 'mutant' - which ends up being a human male. In a weird mix of the Jungian psychological concept of dual-gender traits within each sex, and the biblical tale of Adam & Eve, Gall Force casually proposes that men are mutations between feminine energy and monstrous power. It is likely that this reading of Sonada's scenarios is triggered primarily by the imaging of women in such roles. For example, Alien (1979) and Aliens (1986) are distinguishable mostly because Sigourney Weaver rather than Tom Cruise is battling it out with breeding female aliens and their offspring. The plot-template is standard macho sci-fi action, but the gendered traits of the fictional characters affect the reading of their actions and motivations. Similarly, the bulk of Sonada's work symbolically and ideologically suggests ways of reflecting on our western image codes by confronting us with images of women performing and thinking in ways our western fiction tends to avoid, suppress or reject.

-

Buichi Terasawa

Cobra, Midnight Eye Goku

Many of the futuristic 80s animations collectively cast their shadow into the spectacularly destructive Hollywood terrain of Alien and Mad Max (both 1979); The Thing and Bladerunner (both 1982); Blue Thunder (1983); Ghostbusters (1984); The Terminator (1985); and Aliens (1986). These are key western films which feature a metropolis exploding due to some sort of technological, extraterrestrial or cybernetic force brought to bare on the city - a key theme which postwar Japanese entertainment has embraced and recodified under post-apocalyptic terms. Buichi Terasawa cuts a line which bypasses this zone of influence. Instead, Terasawa reworks and realigns a less urban and more urbane line of figures: from Sean Connery's James Bond to Clint Eastwood's Man with No Name to Jean Paul Belmondo's many professional criminal portrayals. And just as the orgy of destruction in big budget Hollywood action movies can be viewed as complex impulses traceable to the final solution America employed by using atomic warfare against Japan, so does Terasawa's cool heroes remind us of the samurai genre of Japanese cinema - particularly the internationally renowned work of Akira Kurosawa. As is well known, while Kurosawa often based his samurai sagas on Shakespearian epics (the Macbeth rewrite of Throne Of Blood, 1957, being most notable here), Italian director Sergio Leone was moved to cast his 'man with no name' character in the same mold from which came Kurosawa's Yojimbo (1961).

Many of the futuristic 80s animations collectively cast their shadow into the spectacularly destructive Hollywood terrain of Alien and Mad Max (both 1979); The Thing and Bladerunner (both 1982); Blue Thunder (1983); Ghostbusters (1984); The Terminator (1985); and Aliens (1986). These are key western films which feature a metropolis exploding due to some sort of technological, extraterrestrial or cybernetic force brought to bare on the city - a key theme which postwar Japanese entertainment has embraced and recodified under post-apocalyptic terms. Buichi Terasawa cuts a line which bypasses this zone of influence. Instead, Terasawa reworks and realigns a less urban and more urbane line of figures: from Sean Connery's James Bond to Clint Eastwood's Man with No Name to Jean Paul Belmondo's many professional criminal portrayals. And just as the orgy of destruction in big budget Hollywood action movies can be viewed as complex impulses traceable to the final solution America employed by using atomic warfare against Japan, so does Terasawa's cool heroes remind us of the samurai genre of Japanese cinema - particularly the internationally renowned work of Akira Kurosawa. As is well known, while Kurosawa often based his samurai sagas on Shakespearian epics (the Macbeth rewrite of Throne Of Blood, 1957, being most notable here), Italian director Sergio Leone was moved to cast his 'man with no name' character in the same mold from which came Kurosawa's Yojimbo (1961).Terasawa's cool cult character Cobra (manga 1977; film 1982) came in the midst of a glut of post-Star Wars space sagas and robot dioramas, and staked a clear claim for a Japanese-European dialogue of style. The manga for Cobra is a quirky mix of Tezukian wonder and Playboy magazine illustration. The film (titled Space Adventure Cobra) is quite different, as the Tezuka sensibility is stronger and the women are rendered in a more overtly shonen style of eroticism, with swirling landscapes of colour and abstracted shapes. It is this fusion between Japanese and European aesthetics that makes Space Adventure Cobra so scintillating. Midnight Eye Goku (manga 1979?; OVA) is a further development of this James Bond-styled character who is not a superhero typical of the America comic kingdom, but a sharp and witty loner. Later works by Terasawa, though, are inversions of Cobra and Goku. In his two most notable works - Raven Kabuto (manga 198?; OVA 1991?) and the recent manga Takeru (1992) the eponymous heroes are overtly and visibly more Japanese, and as such qualify a distinctive post-Samurai heroism. While many other Japanese manga artists and animator-directors have concentrated on working within the manga and anime industries - developing print and film/video media - Terasawa displays an enthusiasm for all forms of computer technology. This has lead him to do as much work in computer games and CD-ROMs. His latest manga - Takeru - was produced by scanning his line artwork and using digital paint and image tools to complete a full colour manga from his home studio. Currently he is looking at ways in which similar technologies can allow him greater artistic control over the complex hierarchy of animation production.