Dumb About Japan

Dumb About Japan

Contextualizing Dumb Type's Memorandum

published in Mesh No.17, Melbourne, 2004It must be boring for Japanese artists to be asked why they foreground technology every time they touch something electronic. It’s probably as boring as hearing archaic European binaries applied to Japanese culture by westerners wishing to scrutinise the supposed mystery of Japan – old but new, past but present, etc.

Not surprisingly, a reflux has occurred in much recent contemporary Japanese art where artists – some ironically, some surreptitiously – project back to western audiences a hyper-iconic manifestation of these blunt binaries. This critical realm will require investigation as it is likely to produce new formations on delocalised art practices and viral ambassadorial influxes across the western globe (not dissimilar to the established spread of manga and anime).

Apart from the breadth, depth and success of their work over the last 15 years, Kyoto theatre group Dumb Type are a vital example of how the East/West connection is both problematised and divined within contemporary arts spheres. On the surface, Dumb Type are an Asian sublimation of the deconstructed Eurocentric grandeur which throbs at the core of epic productions by Robert Wilson, Laurie Anderson, et al. Yet the high-art staging of operatic spectacle which was heightened as postmodern effect within the Brooklyn Academy productions is transmuted within Dumb Type’s presentations.

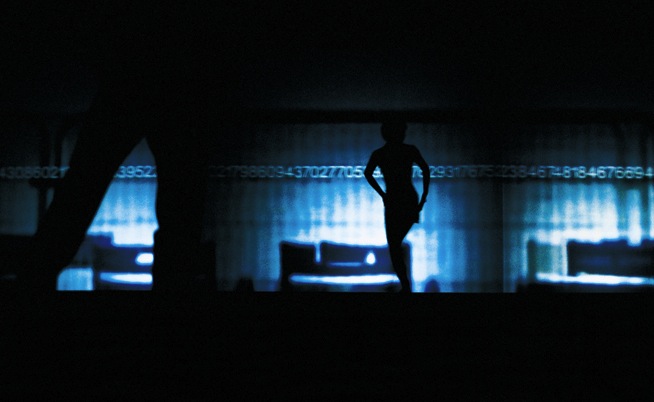

Memorandum (1999 – presented at Melbourne Arts Festival, 2003) is possibly the best example of this as it is a proscenium theatre work in contrast to Dumb Type’s earlier and manifold expanded theatrical production. Memorandum textually is figured around the interfacing of memory and memos: it is not ‘past but present’, but rather an eventful simultaneity that fuses the temporal distinctions between that which is before and that which befalls. High-spectacle definitely reigns in Memorandum but it does so less on a planar axis of scale and frame, and more through the non-linear verticality of audiovision, where sound, image and event are conjoined for experiential impact.

Memorandum ‘transmutes’ 80s postmodern theatrical spectacles by de-narrating and effectively silencing the arch stylisations over which the postmodern fawns. As a kawaii (‘cutie-pie’) voice murmurs “mmmm ... maybe ... it's about Goldilocks and the Three Bears … maybe” during the opening of Memorandum, signification and meaning are rendered flat and floating like transparent sheets: this is not a narrative with classical depth, but rather a liquefied palimpsest of disembodied sensations and connections. The whole of Memorandum indeed is a ‘maybe’ story, but one which idly ponders if in fact it is itself about Goldilocks or not. True to Japanese pseudo-assertive protocol (where the ‘maybe’ or “ano …” is deliberately left hanging in the discursive air), Memorandum is less about statement and more about understatement. Silences, resonances and reflections embody deeper tonality in clear line with Dumb Type’s agenda of ‘dumb media’. Yet the importance of this theatrical textuality is to sidestep the bad binary of prose-versus-poetry, rather than merely celebrate acts of sensual visualisation to which contemporary European theatre still perceives as avant-garde. Memorandum is undoubtedly poetic, but it does not present poetry as an escape from prose.

Memorandum has been misread in many lauded instances as a Japanese version of European ‘image-theatre’ (which itself is influenced poorly by traditional Japanese theatrical forms like bun raku, kabuki and noh). That’s like saying James Brown is influenced by Britney Spears. Memorandum is in fact a very traditional Japanese theatre work – which is both its power and beauty. The staging in many moments is a perspectival recreation of the 17th Century folding screens across which landscape paintings unfold. Dumb Type reinvent these as translucent screens which merge between video-projections and spot lit-apparitions of live performers, creating a peculiar sense of dimensional depth and focal shift typical of Japanese folding screens. ‘Upon’ this visual plane is laid a soundtrack (by Ryoji Ikeda) that applies a sonic version of Sergei Eisenstein’s montage principles, which then becomes less a comment on synchronism as per Eisenstein’s notions, but more a comment on asycnhronicity within the Japanese tradition of musical structure.

As with much Japanese cultural manifestations, the mode of ‘reading’ required is one attuned to the interrelationship of parts - not as some Frankensteinian assemblage, but as a mode of ‘inbetweening’ where totality is always apparent. Within a global perspective then, works like Dumb Type’s Memorandum are a potent realization of the rhetoric of ‘total theatre’ wherein there is neither old nor new, past nor present. For there possibly is neither East nor West anymore. This is the memo received from Dumb Type.

Text © Philip Brophy. Image © Dumb Type.