Graphic Cinema

Graphic Cinema

published in Artlines 2011 - issue 4, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 2011

Cinema lacks so much – for which it overcompensates. Being a hybrid form that synthesizes photography, theatre, literature and music into a spectacular mash-up of sensations, cinema makes the most of its multiple derivations. So if cinema has no originating form as do most traditional arts, it makes sense for it to use anything as a basis for making a movie.

Comics are perhaps the most obvious template for cinema’s chimerical nature. The comic page – a fusion of Cubist structure, Russian montage principles, Eastern ideographic line-work, stereotypical characterisation, and ruptures between objective description and subjective sensation – reads like a script for a type of proto-cinema. Whereas novels are poetic, cerebral and wordy, comics unleash dynamic, explosive and heightened narration. In comics, the act of ‘reading’ is a stretched metaphorical procedure: your eyes dart all over the page while you link narrative fragments in an improvised ‘writing’ of the story in your own mind.

It is strange that ‘the graphic’ is such an unwelcome notion in cinema. From the idea of extremities invoked by depictions of graphic violence, to the assumption that drawing and inking are poor cousins of the supreme act of painting, cinema confers an unspoken restriction on modalities associated with the graphic. Partly this arises from cinema’s photographic mandate: it films rather than fabricates, shows rather than illustrates. Yet anyone can philosophically or technologically argue that cinema is no reality machine – and indeed, that it progressively undermines such old beliefs. The entrenched division from ‘real photo-cinema’ and ‘graphic stylised movies’ is more accurately situated in the genealogy of comics: their lowbrow status is rooted in delivering content in the broadest of strokes. Yet viewed in a more giving light, comics constitute a poetic vernacular, wherein language is condensed and abstracted, and image is allowed to cohabitate the printed page.

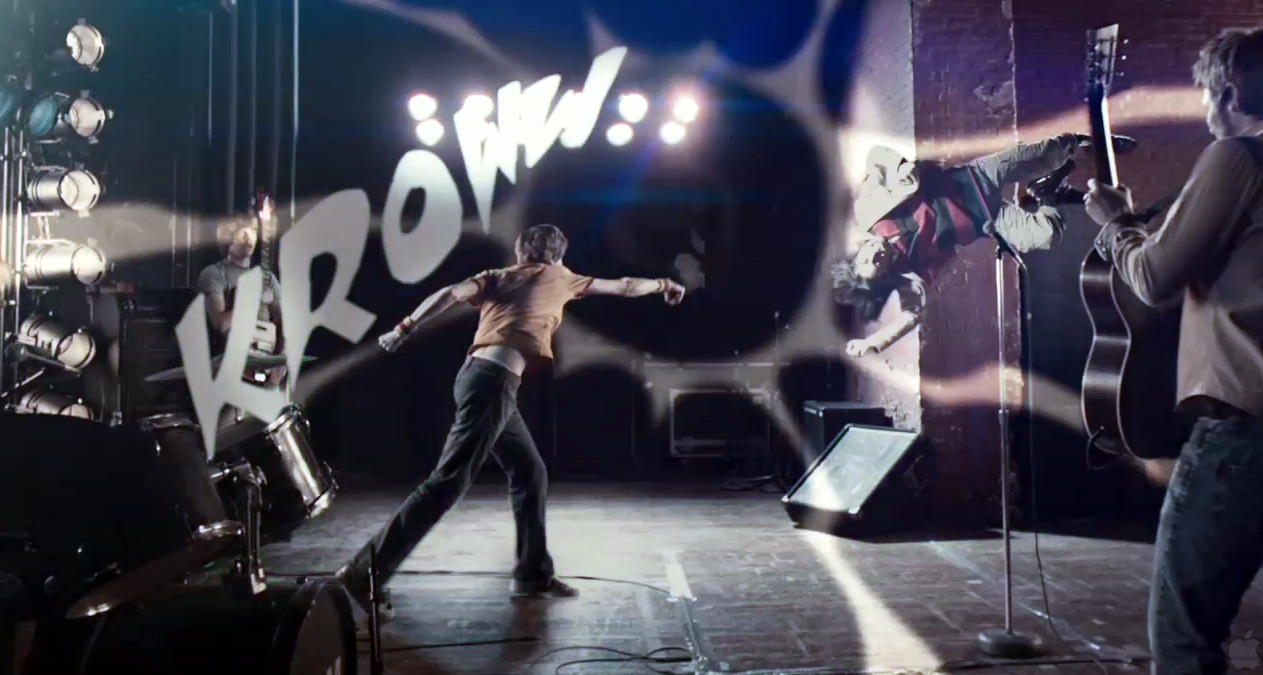

When cinema perceptively embraces the sensibilities it shares with comics and graphic novels, great stuff happens. In Zack Snyder’s Watchmen (2009, based on Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s graphic novel series), a densely self-mythologizing narrative simultaneously critiques ‘super hero’ ideology while fabricating a wildly cosmological movie. In Edgar Wright’s Scott Pilgrim vs. The World (2010, based on Bryan Lee O’Malley’s ’s graphic novels), the ‘real world’ of Toronto locales randomly and violently transforms into stages for hyper-emotional teen angst battles of love. And when Robert Downey Jr. embodies the ludicrous mix of filthy rich philanthropy and cynical hi-tech research, Jon Favreau’s Iron Man (2008, based on Stan Lee’s comic series) becomes a cunning implosion of altruistic histrionics.

Granted, these brief examples reap the benefits of a bounty of experiments and follies courtesy of modern Hollywood’s exploitative love affair with the pulpy merchandise-ready comic medium ever since Warner Bros. let Tim Burton run wild with Batman back in 1989. But whereas family franchises like Lord Of The Rings and Harry Potter reduce cinema to the rudimentaries of comic narrative while distracting us with painterly (not graphic) CGI simulations of Renaissance-era landscaping, other movies push cinematic form into new territory by acknowledging the legacy of comics and their graphic impact. When the two set up such a dialogue, it's a win-win situation.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © respective copyright holders.