More Priapic Than Haptic

More Priapic Than Haptic

Marcel Duchamp's Etant donnes

published in Australian New Zealand Journal of Art, Vol.11 No.1, Brisbane, 2011I never liked Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (aka The Large Glass) (1915-1923). Its wilful impenetrability, its pretentious titling, its ungainly posture, its unrewarding hermeticism, its clinical scripture, its affected play with materialism, its Francophiliac punning, its alchemical mythology. Yet note how accurately my litany of complaints describes the critical contours of conceptual art within modernist (and postmodern-revisionist) contemporary art practice. Maybe this is that work’s lasting legacy: it consolidated (and continues to do so) the lazy way in which self-tagged conceptual art presumes it can ‘be conceptual’ courtesy of The Large Glass.

But I never gave up on Duchamp. There were always ruptures, breakages, “stoppages” in his trajectory which continued to fascinate me. The gulf between Nude Descending A Staircase (1912) and Urinal (1917) alone gave cause to ponder the stretched possibilities between conceptualising the material and materialising the conceptual. Indeed, it is this irrevocable bind of the two forces – of their propensity to become the other but without dissolving that bind – that Duchamp’s work elucidated better than the irritatingly glib type-written aphorisms of so many conceptual artists in his wake.

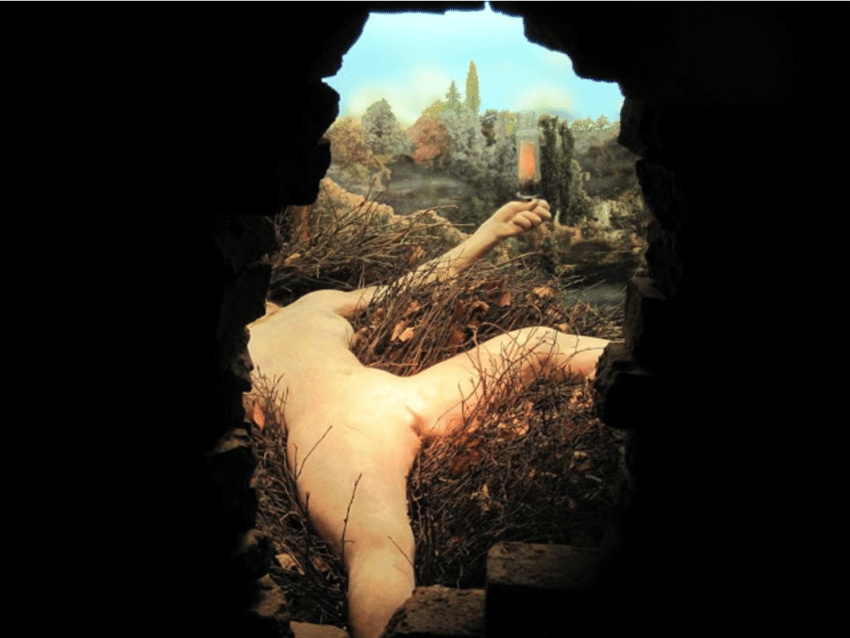

I’ll never forget the first time I saw a small reproduced image of Duchamp’s Étant donnés (1946-66). It would have been around 1977 when I was 17. Its plain filthy allure – titillating, guttural, fetid, morbid – spoke volumes to me as I scrutinised the meagre reproduction. The available discussions of the work for decades later did little to grapple with this mysterious thing and its ‘thingness’. Its blunt opposition to The Large Glass excited me. The Large Glass had been so over-explained (by both Duchamp and his American and British championers) as to reveal the project to be in the spirit of alchemy, a fool’s gold for philosophical pondering. Étant donnés oppositely generated confused responses by those who experienced this controlled exposition of palpable consumption.

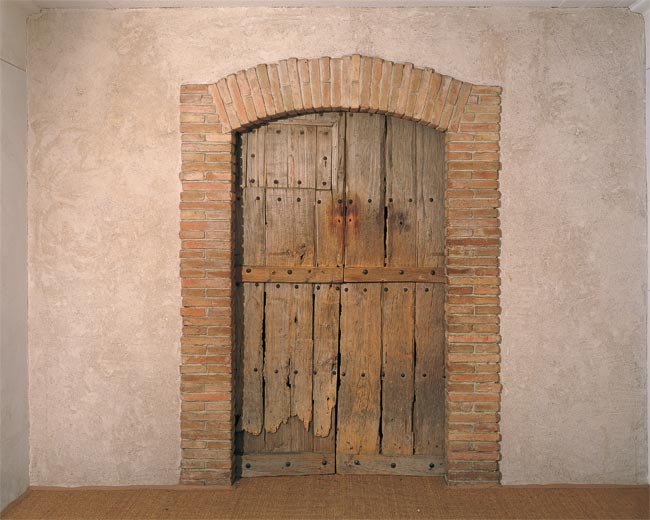

Best of all, Étant donnés cast doubt on the sexuality of Duchamp – not his persuasion per se, but his handling of it within his artistic endeavours. This major work’s employment of a frighteningly realistic mannequin, head hidden, vagina exposed, and its installation’s hyper-controlled scopic parameters thrust Duchamp’s sexual proclivities into your retina. He may have had ‘forgotten to paint with his hand’, but his penis kept working, generating a priapic work in revision of his recognized haptic objects and images associated with his surrealist productions. The 343 page hardback tome published by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Marcel Duchamp Étant donnés (2009, edited by Michael R. Taylor), wonderfully complicates everything you thought you knew about Duchamp but were too hung-up to ask. Through a series of insightful essays – all robustly academic, scholarly and/or technical, and refreshingly devoid of limp theoretical posturing – one comes into phantom contact with Duchamp’s member.

The book is lavishly illustrated, though not in a way that normally befits such a description. For in place of the erotic hi-resolution of cum-inferred grain which defines the coffee-table art-book, this weighty catalogue is like that scene in any typical serial killer movie when the police uncover his lair to discover the extent of his obsession. Through extensive documentation of each and every element which led to any stage of the production of Étant donnés, one is half-chilled/half-thrilled to see how this singular image seemed to have scarred Duchamp’s inner retina. His naïve grappling with a myriad of eclectic technologies and folk-like approximations of their effects places him nearer to the compulsion evident in Hans Bellmer’s amateur snaps of mutating self-anthropomorphicising dolls and Henry Darger’s wall-papered tracings of pre-pubescent girls being butchered by marauding soldiers. In a pre-Chapman era, Bellmer and Darger were compelled to fabricate their traumatising muses by whatever means they could; Duchamp likewise fiddled with wax, plaster, twigs, batteries, fluoro-tubes, paint, wires, dime-store parts and trash dumpster bits to bring his nameless headless figure to life.

In this sense, the book is properly forensic. I fantasise it to be not that different to conservators’ reports undertaken for the auctioning of Gustav Corbet’s L’Origine du monde (1866) (a work that Duchamp in the 70s had drolly mentioned to be a particularly important work in the history of modern art). There are pages of discussion on the painful fabrication of the figurine from plaster casting, mould inversions, latex skin applications and rickety internal armature. It reads partly like an autopsy on an extremely precious discovery, and partly like a Frankensteinian experiment in bringing a corpse to life. How fitting that Duchamp himself provided the infamous ‘manual’ which detailed every facet of the work in terms of inventory, installation, maintenance and presentation. Duchamp perversely held to an insatiable Pygmalion drive in spite of his ascetic penchant for plain spaghetti and chess.

The book’s relentless fix on the materiality of Étant donnés is what makes this such an invaluable contribution to modern art as we thought we knew it. Here is the key artist who pumped modernism’s chauvinistic throbbing veins with a conceptual adrenaline so as to render its body immobile and incapable of visual spectacle. And here is that same artist whose last work – developed in private isolation, shrouded by deliberate disinformation, yet comprised of numerous cryptic signs released to the art world throughout its 20 year gestation – replicates and reinvigorates the same egocentric impulses which his career seemed intent on destroying. Far from ‘forgetting with his hand’, Duchamp continued to practice and perfect a variety of traditional mimetic crafts in order to make one of the 20th Century’s most un-abstract counter-cerebral art works. That naked spread-eagled female reclining on twigs, holding a lamp in a setting straight from a Swiss chocolate tin is violently conservative. And being forced into a voyeuristic encounter with the work through its peep-hole aggressively manipulates one’s scopic experience in a way that runs counter to a half-century’s worth of ‘shock-of-the-new’ barrier-breaking.

The artwork Étant donnés is Duchamp’s own self-published Hollywood Babylon. Like Kenneth Anger’s inimitable excavation of the sad and sordid mortality of golden era Hollywood stars, Étant donnés is Duchamp archiving and preserving both himself and his obsessions. The book notably details his relationship with the vibrant artist Maria Martins (herself no wallflower when it came to making violent sexual works of Amazonian might) and how part of the existing mannequin’s original model was Martin herself by whom Duchamp was stricken. After a brief and one presumes fiery romance, Martins moved on, leaving Duchamp with a cast of her body and many an unanswered love letter. Étant donnés then is less a morbid study and more an elegy to his lost muse. Just as Kenneth Anger detailed the material corporeality of his faded Hollywood stars’ erotic delusions, Étant donnés reinstates Duchamp’s conceptual operations as being fuelled by the most sexual of concerns.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © Marcel Duchamp estate & Philadelphia Museum of Art.