Terror In A Room

Terror In A Room

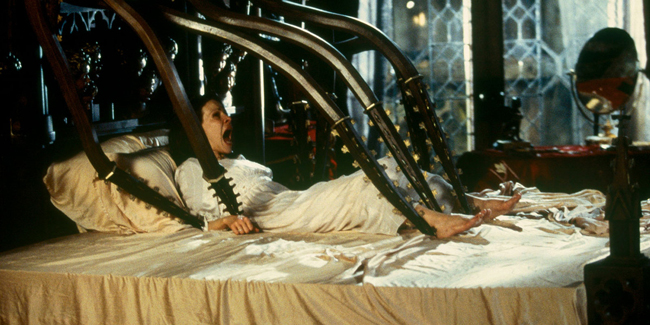

The Haunting

published in Real Time No.33, Sydney, 1999Sound. The very mention of the word shifts the gears of the unconscious: you know I'm talking about something to which you pay neither heed nor attention. So circumscribed is sound by our desire to mute its neumonic life, we do not realize how much we curtail its occupancy of our conscious experiential terrain. In psychoacoustics, 'perceptual masking' refers to our ability to filter unwanted frequencies so as to focus on those we wish to selectively register (say, ignoring the din of restaurant chatter while we listen to the single voice of a friend). The unaccounted reflex of this phenomenon is that we may be now less engaged in active listening and more committed to suppressing the sound around us. This is the crux of why sound is so ignored - not because the visual is so dominant an incursion of the mind, but because we spend so much neural energy trying to become unconscious of unwanted sound.

But why the desire to silence? We were never silent. We were never in silence. The world rings, hums, intones, vibrates - not in any para-mystical way (as proposed by so much voguish scientific wondering by sound artists, composers and architects alike), but in a swirling and shifting sono-synoptic chart which documents less the cosmos and more our banal existence. To rephrase Alvin Lucier, a room is sitting in me: the low hum of a fridge on wooden floorboards; the soft chorale of blow wave heaters; the high climb of a distant septic tank. I'm doing nothing; I think I'm being quiet, but my externalised extemporized self is cooling food, getting warm, emptying body wastes. I am my environment in the most subliminal way, and I do everything in my power to pretend I am neither present nor actively producing sound.

In fact the modern age is one of terrible ambience where acoustic mass is deafening not in volume but in its very diffusion. Those who have consciously criticized noise - music in shops, unattended car alarms, truck routes near houses, etc. - have focussed (far too obviously) on rupturing sonic incidents, yet no one is venting rage against air conditioning, hard drives, exhaust fans or numerous other layerings of pink noise which we tune-out as background texture to our urban toil. Ironically, just as sound art installations veer toward the amorphous and the immersive as a tactic to make one 'aware' of the pleasure of sound, so does art culture contribute to the same creeping engulfment of beds, sheets and curtains of noise which decorously coat the architecture of our domesticity. Wake up, people. Sound no longer bombards us with detonated bursts and shards: it slowly infects us with its acoustic patina of unassuming nothingness.

In this sense, the domus need not be rendered Gothic, baroque or ornate to conjure a sense of dread. Spooky movies about haunted mansions essentially invert the somnambulistic state in which we habituate our personal spaces. If we were suddenly made aware of all the tones and tunings which comprise the residue of our everyday activities, we would find our tremulous homes as terrifying as Hill House in Jan du Bont's The Haunting (1999). Here is another nightmarishly over-designed special-effects movie which should keep digital nerds and interior decorators moist for 28 days and audiences distracted for 28 seconds, but the role of the sound in this film amplifies much about the way we perceive and/or ignore the insignificance of acoustic auras. For as baroque as the visual design in the film is (and believe me, it makes Disneyland's Haunted Mansion look like a shopping trolley at K-Mart), its ocular loudness is no match for the way the sound design forces its way through our optical algae and pierces our carefully guarded aural consciousness.

An early moment in The Haunting touches this taut gauze stretched between sound and image. Eleanor (Lili Taylor) is wakened by three soft off-screen thumps, which she dozily presumes to be her now-departed ill mother banging the wall for aid. Three more bangs, which we audit as unreal and unearthly. Then three more bangs which shake the cinema auditorium to the point of collapse: both Eleanor and us know something exists beyond the sonic. Those three layers of big bangs illustrate what could be posited as three levels of aural consciousness: the displaced referential (all the sound we don't listen to); the forced ethereal (that same corpus of sound rendered noticeable); and the inverted inescapable (the realization that we might not be able to ever unlisten to sound). Illogically vacillating between a fear of silence or a dread of deafness: that is truly spooky. Time and again, I pictured myself in The Haunting, quivering inside Hill House's labyrinth of colonic chambers as monstrously invisible presences resonate its EC comic architecture and rattle its Escher-like architraves. Time and again, I imagined myself trapped in that state of being unable to not listen to everything which I selectively filter so as to focus, concentrate, be at ease, remain sane.

When the evil Ukraine (who possesses the house) first marks his presence, the off-screen pounding I swear rattled the light fittings and air-conditioning ducts of the cinema. Granted that Gary Rydstrom's sound design went for the now-prerequisite subsonic rumbles, his orchestration of sound effects was nonetheless masterly in its precision of frequency and its intent to make the sound bigger than either screen or auditorium might handle. This hyper-fantastic aesthetic to the sound design is ultimately ironic, in that on numerous occasions, characters in the film query each other - "Didn't you hear that noise?" - which occurred at deafening decibels in the very next room. All rhetoric of plausibility fades as the sonic purpose of the film is not to describe a reality or portray a psychological state, but to unnerve the audience - to go beyond the screen and into us. To transgress the sanctity of our own deliberated nerve deafness.

More importantly, the complexity by which a film these days must achieve such results has little to do with earlier constructs and paradigms of sound design. From the searing silence of Jack Clayton's The Innocents (1960) to the claustrophobic quietness of William Friedkin's The Exorcist (1971), spooky sound design has hitherto been based on drastic binaries of silence/noise. The Innocents is an unapproached landmark in this regard, where the most disquieting moments occur in a silence which replicates a disequilibrium of the senses, creating the sense of hearing nothing as one verges on the brink of trauma. Conversely, The Exorcist uses harsh sound editing to render the domestic environment as a potential hell before any satanic forces become manifest, demonstrating great skill in foregrounding aural manipulation to prepare the way for the visual outrage to follow. But in a contemporary climate where a million pink noises colour the world a fleshy body of heaving ambience, the on-off tricks of sound editing fast loose their power in the cinematic realm. The Haunting signposts the paths to be taken in order to reinvest the cinema with the power to psycho-acoustically make us cogniscent of the comforts we find in own aural purgatory.

Text © Philip Brophy 1999. Images © United International Pictures