Horrality

Horrality

The Textuality of the Contemporary Horror Film

published in Art & Text No.3, Melbourne, 1983reprinted (with preface) in Screen UK, Vol.27 Nos.1/2, 1986

reprinted in THE HORROR READER, Routledge, London, 2000

reprinted in GOTHIC: Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies, Routledge, London, 2004

1985 reprint - preface

"Horrality" was written in mid-'83 during what appears to have been (on reflection) the peak of a small 'golden period' of the contemporary horror film. The article serves as a general introduction to certain characteristics of the contem¬porary horror film which distinguish this particular phase of horror from previous ones. The act of showing over the act of telling; the photographic image versus the realistic scene; the destruction of the family, the body, etc; and a perverse sense of humour all go toward qualifying these films as contemporary, both in terms of social entertainment and cinematic form. The following two and a half years has seen many new deve¬lopments, from the hysteria surrounding 'video nasties' to the maturing of many horror auteurs. Serious discussion is then needed on, respectively, the politics of taste (what makes one able to not able to watch a horror movie?) and personal tonalities of the genre (how does one film-maker sustain thematic continuity within a genre about genre?). And even that would be pruning our problematics. The horror film could very well hold many keys to problems which the cinema will be addressing (or avoiding) for some time to come: How does one qualify genre now? What effects have the dichotomies of horror/terror and telling/showing had on the development of cinematic language? What are the relationships between certain aspects of porno¬graphy and certain aspects of the cinema? What defines our notion of special effects in the cinema? How does one provide a critical voice for exploitation in the writing of the history of the cinema?

'Horrality' does not even get to ask these questions, but rather points out that something different is happening in these films. We're only on the front porch of a monstrous mansion full of critical zombies waiting to be awakened and engaged. Soon enough - we'll be in the basement.

The Word

Phrases are coined; terms are invented; metaphors are employed. The invention of language always carries a blasphemous tone, be it comical, opportunistic or hypothetical. The invention is devoid of linguistic validation though the effect is unavoidably semantic. The neologism exercises language as the utility that its design describes. It is said that there has already been a word invented for everything that needs to be said. By the same token, some new things that need to be said need new words invented for them.

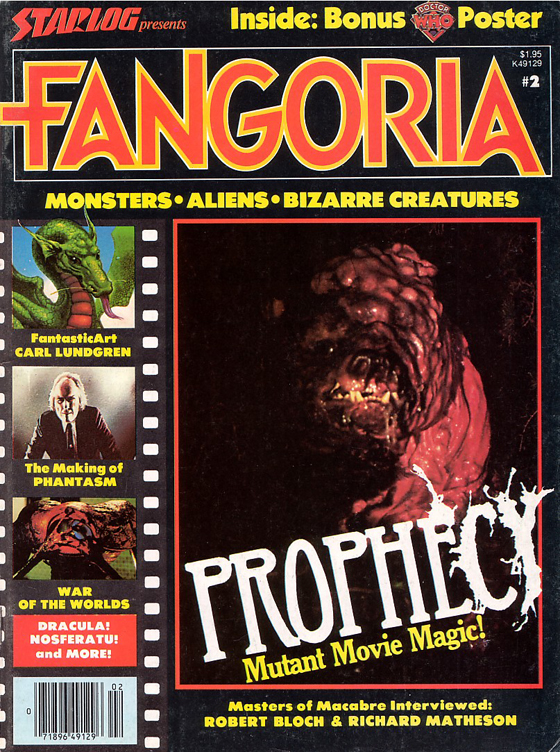

In August 1979, the first issue of the American magazine Fangoria was released. It is a bi -monthly magazine devoted to horror movies. The title speaks volumes: gore, fantasy, phantasmagoria, fans. It simultaneously expands a multiplicity of cross-references and contracts them into a referential construct. This semantic effect strangely echoes the relation¬ship between the emergence of Fangoria and the development of the contemporary horror film, whereby an ever-growing cult journal expands and contracts a critical voice for a mutant market-that of the contemporary film: a genre about genre; a displaced audience; a short-circuiting entertainment.

Another word is invented. More pretentious in tone and more theoretical! in intention: 'Horrality' - horror, textuality, morality, hilarity. In the same way that Fangoria celebrates the re-birth of the Horror genre, 'Horrality' celebrates the precise nature of what constitutes the films of this re-birth as texts. As neologisms, both words do not so much 'mean' something as they do describe a specific historical juncture, a cultural phase that is as fixed as the semantic accuracy of the words.

The Object

The modern horror film is a strange animal. A camouflaged creature, it has generally been accorded a less than prominent place in the institution of the Cinema, due mainly to the level at which its difference (its specificity, its textuality) is articulated. It is a genre which mimics itself mercilessly-because its statement is coded within its very mimicry. Increasingly throughout the first half of the Seventies, the Horror film defied itself, distancing itself immensely from what historically had been defined as the genre, incorporating the hey-days of the Universal, Hammer and Toho studios and the legacy of Roger Corman and Herschel Gordon Lewis. To make a broad distinction, the Seventies have heralded a double death for Genre in general, as critically and theoretically it became a problematic which more and more could not bear its own weight, and, in terms of audiences and commerciality, it was diffused, absorbed and consumed by that decade's gulping, belching plug-hole: Realism. Nonetheless, Horror films were always being made, though their attraction was usually minor, punctuated by mainstream successes that provided well-crafted Horror: The Abominable Doctor Phibes (1971); Last House on the Left (1972); The Exorcist and Sisters (1973); and Carrie (1976), for example.

However, it was the transition period between 1978 and 1979 that clearly announced the rebirth (at least popularly if not also critically) of the Horror film, culminating in (i) the mainstream successes of Halloween (1978), an independent production made by newcomer John Carpenter, and Alien (1979), a big-budget production by another newcomer, Ridley Scott; and (ii) the cementing of the underground status of George Romero with Dawn of the Dead (1979) and David Cronenberg with The Brood (1979). The historical door of the Horror genre was reopened, allowing discovery of Romero's Martin (1978), The Crazies (1973) and the classic Night of the Living Dead (1968), as well as Cronenberg's Rabid (1977) and Shivers (1976).

In 1983 the contemporary Horror film is definitely a felt presence, with the never-ending onslaught of Horror films reaching large audiences, a rejuvenation of the Drive-In circuit, the rise in video libraries and the increasing value and relevance that the genre currently holds not only for mainstream film audiences but also for rock culture and film culture. A major problem still exists, though, in the domain of mainstream film criticism (i.e. taste arbitration for those who would 'benefit' from it) and film distribution, where the former has no critical language to encompass the contemporary Horror film while the latter is ignorant of the marketing potential that these mms have. Thus, the bulk of my horror film viewing over the past four-five years has consisted of Drive-In doubles, Dusk-to-Dawns and hired video cassettes. (Most of these films do not reach a cinema theatre in Australia.) It is this state of affairs that constitutes the displaced audience of the contemporary Horror film.

My first problem (among many) in speaking of the textuality of the contemporary Horror film is in dislocating it from its more traditional generic overtones. It is a stratagem that involves handling the films them¬selves like freshly severed limbs: objects born on their own and obviously fragmented. A history of generic study already clothes the Horror genre, encompassing the politics of (films like) The Invasion of the Body Snatchers; the philosophy of (films like) The Incredible Shrinking Man; the sexuality of Dracula; and the morality of Frankenstein. The fantasy film in general has provided a morphology of the metaphor, an endless commentary on humanity in its aspirations, implications and complications. At its most conventional, the genre is worked as being a formalist catalogue of mythological writings that organically and historically form the growth of the genre. It is such a growth that critically lays down the notions of origins (from Mary Shelley to Transylvania to Witchcraft); actors (from Karloff and Lugosi to Cushing and Lee); auteurs (from Roger Corman to Terence Fisher); and sub-genres (Vampires, Created Life Forms, Ghosts, Mummies, Zombies, Monsters, Aliens, Demons Werewolves, etc).

It is not so much that the modern Horror film refutes or ignores the conventions of genre, but it is involved in a violent awareness of itself as a saturated genre. Its rebirth as such is qualified by how it states itself as genre. The historical blue-prints have faded, and the new (post-1975) films recklessly copy and re-draw their generic sketching. In this wild tracing, there are two major areas that affect the modern Horror film: (i) the growth of special effects with cinematic realism and sophisticated technology, and (ii) an historical over-exposure of the genre's iconography, mechanics and effects. The textuality of the modern horror film is integrally and intricately bound up in the dilemma of a saturated fiction whose primary aim in its telling is to generate suspense, shock and horror. It is a mode of fiction, a type of writing that in the fullest sense 'plays' with its reader, engaging the reader in a dialogue of textual manipulation that has no time for the critical ordinances of social realism, cultural enlightenment or emotional humanism. The gratificaction of the contemporary Horror film is based upon tension, fear, anxiety, sadism and masochism-a disposition that is overall both tasteless and morbid. The pleasure of the text is, in fact, getting the shit scared out of you - and loving it; an exchange mediated by adrenalin.

'Horrality' involves the construction, deployment and manipulation of horror - in all its various guises-as a textual mode. The effect of its fiction is not unlike a death-defying carnival ride: the subject is a willing target that both constructs the terror and is terrorised by its construction. 'Horrality' is too blunt to bother with psychology-traditionally the voice of articulation behind horror - because what is of prime importance is the textual effect, the game that one plays with the text, a game that is impervious to any knowledge of its workings. The contemporary Horror film knows that you've seen it before; it knows that you know what is about to happen; and it knows that you know it knows you know. And none of it means a thing, as the cheapest trick in the book will still tense your muscles, quicken your heart and jangle your nerves. It is the present - the precise point of speech, of utterance, of plot, of event - that is ever of any value. Its effect disappears with the gulping breath, the gasping shriek, swallowed up by the fascistic continuum of the fiction. A nervous giggle of amoral delight as you prepare yourself a totally self: deluding way for the next shock. Too late. Freeze. Crunch. Chill. Scream. Laugh.

The Effect

When the 'R' certificate was first introduced to Australia, one particular movie that was strongly linked to the titillation caused by this moralistic parental censorship was The Exorcist (1973). Swamped with gore, it was what has now come to be the ultimate Drive-In movie: an opiate of adrenalin. Historically, its controversy was, among other things, due to it being one of the first instances of the whole family being subjected to graphic gore, unadulterated horror and fantastic violence. But none of it was gratuitous. The Exorcist was a tale of Catholic morality (Good vs. Evil) that utilised state-of-the-art gore techniques to produce a work which thrust its audience into a vertigo of realism - the real of its depiction and the real of its fiction. It was a film that was culturally situated in a time when demonic possession was one of those mysteries that threatened the social parameters of the real, of the truthful. One entered into the cinema not for a fiction, but for a direction on that particular social debate. One left confused by the initial vertigo, a two-pronged dilemma - not only 'how did they do that?' but 'do such things exist?' The fiction undercut itself, impregnating its effect with plausible existence.

In 1980, The Amityville Horror was released. It ironically (but dumbly) copied the currency of The Exorcist but went one step further: where The Exorcist was founded on a plausibility mediated by our (inherently religious) fears, The Amityville Horror purported to be a dramatisation of an actual event. This time, yes: it really did happen. Still, the film was as interesting as the News, a type of telling that performs a journalistic dance around its factual base, creating a dun gap between fiction and fact, neither one nor the other. The Amityville Horror occupied such a space, devoid of any perversity in its telling and full of golly-gosh realism. Some years after, the whole thing was proved a fraud - and out came Amityville 2: The Possession (1982). To counter both The Exorcist and The Amityville Horror, Amityville 2 revelled in itself as fiction and went all out to make a horror movie, marking a commercial peak in a growing trend in Horror films, namely the destruction of the Family. Whereas suspense was traditionally hinged on individual identification (the victim, the possessed, the pursued, etc.), it was now shifted onto not a family identification, but a pleasure in witnessing the Family being destroyed-it being the object of the horror and us being the subject of their demise.

The Hills Have Eyes (1977) clearly delineated this by positing two totally opposite families against one another in a battle of horror and fight for survival. An all-white all-blond middle-class American family (mom, dad, two teenage kids, grandma, elder brother and his wife) set out on a camper holiday in the mid-west desert. While camped, they encounter an inbred family of cannibals (papa, mamma, son, daughter, grandma and other animals) who kill off the 'white bread' family (director Wes Craven's description) one by one in the most gory ways possible. While The Hills Have Eyes is an unabashed horror-comedy, Amityville 2 situates its horror in a social-realist frame, making it like The Exorcist meets Ordinary People. Continually the family in Amityville 2 is pictorially framed within the screen frame - through doors, by windows, in mirrors, on tables - forever reinforcing the Family as a pathetic Polaroid of complacency, ripe for the total destruction that eventually befalls it.

At the film's end, the fully possessed son methodi¬cally shoots all the members of the family. A strange suspense is generated here: not only is one wondering 'is he or she going to get it?' but also 'how far is this movie going to go?' The film takes pleasure in actually killing off everybody. Hitchcock once regretted having the young boy with the bomb parcel blow himself up on a packed double-decker bus in Sabotage (1936) because the audience (then) was not relieved of the tension created in wondering whether the boy would survive. Amityville 2 - like most contemporary Horror films - has no such regrets.

Perhaps what has been an even more prolific trend is the destruction of the Body. The contemporary Horror film tends to play not so much on the broad fear of Death, but more precisely on the fear of one's own body, of how one controls and relates to it. In 1976, an Italian movie Deep Red made an impact not by portraying graphic violence - a trademark of Herschel Gordon Lewis in the '60s with films like Blood Feast, Color Me Blood Red and She Devils on Wheels - but by conveying to the viewer a graphic sense of physicality, accentuating the very presence of the body on the screen, e.g. scenes where a person gets rammed into a marble slab, mouth wide open in a scream, crushing the teeth on impact. Deep Red is cinematic scraping of chalk on a blackboard. Suspense is set up by knowing that the next scene of violence is going to be uncomfortably physical, due to the graphic feel effected by a very exact and acute cinematic construction of sound, image, framing and editing. But the contemporary Horror film often discards the sophistication of such a traditionally well-crafted handling of cinematic language.

Deep Red in fact functions as a mid-way point between the Hitchcock debt (carried on by DePalma and Carpenter) and the Lewis debt (carried on by the likes of Paul Morrissey, John Waters, Steve Cunningham, Tobe Hooper and Sam Raimi), incorporating a mode that both 'tells' you the horror and 'shows' it. It is this mode of showing as opposed to telling that is strongly connected to the destruction of the Body. David Cronenberg has consolidated himself as a director who almost exclusively works in this field, with films about an artificially created sex-parasite that transfers itself from body to body during intercourse, causing a wild sex epidemic (Shivers, 1976); a mutant cancer growth resultant from a plastic surgery experiment (Rabid, 1977); the birth of a mutant brood by a psychologically unstable mother receiving treatment by a special psychiatrist who promotes the physicalisation of his patients' problems through their bodies (The Brood, 1979); and the awesome physical power that the mind has over its own body and other bodies through para-psychology (Scanners, 1981). Scanners, alone, could rest as the penultimate Body movie, with an opening shot where a 'scanner' -through the pure power of thought - blows another scanner's head apart. And you see it happen. The finale of the movie is something that defies literary description. The horror for such films' subjects is the matter-of-fact nature of the films' plots, as they are slight twists on the fear of getting cancer or even rabies itself. Scanners goes further and incorporates a fear of what amounts to mental mugging, translating the liberal fear of having someone read your mind into someone exploding your head through reading your mind.

Ironically, one of the original exploding-head scenes appeared in Brian de Palma's The Fury (1978) to which Scanners perhaps owes a debt due to both movies dealing with thought-reading more as a physical phenomenon than a spiritual, ethereal experience. The difference between the two films is the incredible sense of theatre used in The Fury; dramatic intercutting between a man violently shaking and a slow zoom in on the girl with the incredible power of ultra-parapsychology is coupled with an equally dramatic orchestral score, bellowing out its crescendo. Cut. Kaboom! Right on cue as the tonality of the symphony resolves itself, the whole body of the man explodes. A true opera of violence, the ending is a stirring cathartic experience that is emotionally charged by its classical construction. On the other hand, the end scene of Scanners is photographic. It, too, has cuts, pans and zooms coupled with an appropriately physical soundtrack of synthesised music, but it centres on what is more of a Transition period of the physique: a metamorphosis of the body. Veins ripple up the arm, eyes turn white and pop out, hair stands on end, blood trickles from all facial cavities, heads swell and contract.

An American Werewolf in London (1981) (despite it being a black comedy that uses its comedy to effect the audience more than its horror) employs the same photographic sensibility to actually show you the transition from Man to Werewolf in real time, as opposed to the ellipse-time of the dissolves of Lon Chaney Jr's face with different stages of make-up signify his mutation. It's not unlike being on a tram and somebody has an epileptic fit - you're there right next to the person, you can't get away and you can't do anything. The Beast Within (1982) sets the stage for such an event as the boy undergoes an agonising transformation on his hospital bed, where a mutated cicada-like creature erupts out of his body, in full view of his mother, 'presumed' father, a doctor, and us. The doctor exclaims 'My God!' (the catch-phrase of the modern horror film) and the mother cries 'My Son!?' The boy not only goes through a transformation, but his body is discarded, shed to make way for the 'beast' within. The horror is conveyed through torture and agony of havoc wrought upon a body devoid of control. The identification is then levelled at that loss of control - the fictional body is as helpless as its viewing subject.

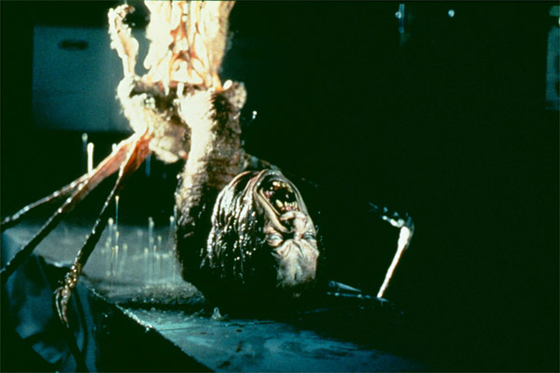

The Thing (1982) took to its logical limit the Body-horror that was initiated in Alien (1979) with that infamous scene where the alien bursts out of a crew member's stomach. Both films deal with the notion of an alien purely as a biological life force, whose blind motivation for survival is its only existence. Not just a parasite but a total consumer of any life form, a biological black-hole. Each film nonetheless generates a different mode of suspense with a similar form of horror. John Carpenter's graphically 'realistic' suspense horror is a world away from Howard Hawks' B-Grade classic, showing everything that the original only alluded to. The essential horror of The Thing was in the Thing's total disregard for and ignorance of the human body. To it, the human body is merely protein - no more.

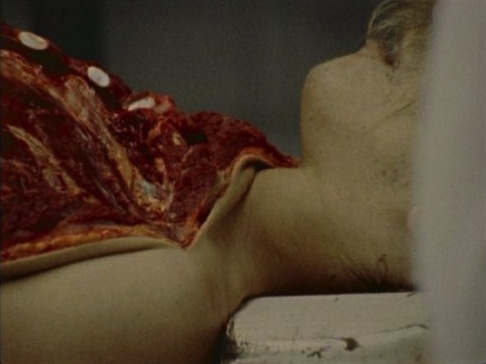

A central scene in the film is when the doctor attempts to revive what is presumed a dead officer but which is in fact the Thing in a dormant phase. The doctor goes to push on the officer's chest but his hands go crashing through the chest like an egg-shell, getting his hands torn off by the Thing's 'jaws' within the chest. The awakened Thing then mobilises the dead body, sprouting tentacles through its flesh and limbs through its muscles in an orgy of gore. But what must be remembered is that the 'original' person has actually died, so that pain and agony is absent. Stan Brakhage's underground art film The Act of Seeing with One's Eyes (1973) deals with a similar effect. Silent and lasting only about 20 minutes, all the footage is shot in a morgue, detailing every method that is used in autopsies in full view for the camera. Lacking any conventional narrative structure, the film starts and ends, a blur of flesh, bone, muscle and tissue that presents the human body in every way except its recognisable forms. Both in terms of its subject matter and its fictional structure, The Act of Seeing with Ones' Own Eyes does not recognize the human body. Likewise, The Thing does not honour any of our beliefs or perceptions of what the human body is.

The Thing is a violently self-conscious movie. In the aforementioned central scene, the biological nightmare that explodes on the doctor's table is shot down in flames - a difficult task as any part of the Thing is a whole lifeform by itself. After all the flesh, blood and guts has been incinerated, the head officer's head lying underneath the table is latched onto by a small bloody tentacle. In what is perhaps the single most technically stunning scene in special effects, the tentacle lashes out of the head onto a door, and drags itself on its side. Just as it reaches the doorway, the crew see it and are transfixed by it. The head slowly turns upside down and, suddenly, eight insect-like legs rip through the head using it like a body. The sight is of an upside-down severed human head out of which have grown insect feet. As it 'walks' out the door, a crew member says the line of the film: 'You've got to be fucking kidding!' Quite obviously, this exclamation operates as a two-fold commentary: (i) the scene portrays the lack of limits that the Thing has in its emasculation of the human body; and (ii) the scene presents to the audience the mind-boggling state that special-effects make-up is in at the moment. Later, the film then presents its most physically effective scene: in extreme close-up, a thumb is slit by a razor for a blood sample. The audience might gasp and scream in the other scene, but in this scene, one's body is queasily affected not by fear or horror, but by the precision that the photographic image is able to exact upon us. The Thing perversely plays with these extensions of cinematic realism, presenting them as a dumbfounding magical spectacle in total knowledge of the irreducible effect that is generated by their manipulation.

The contemporary Horror film in general plays with the contradiction that it is only a movie, but nonetheless a movie that can work upon its audience with immediate results. As such, it is only the result that counts. A film like Ghost Story (1982) even names itself - its design and function - in its very title. Within the fiction, four old men form a 'chowder society' as a regular social occasion to tell each other stories for the sole purpose of scaring one another. Out of this unfolds the central story, which is designed to scare the viewer. All stories engulf one another in a whirlpool of fright generated by the act of telling. The opening of The Fog (1980) sets a similarly quaint scene: an old fisherman is camped out on the beach at night with a group of kids aged between seven and ten, their awe-filled faces lit by the flickering camp fire. In this Norman Rockwell setting, the fisherman tells the local folklore tale about the curse put on the town by pirates who were killed by the prominent townsfolk a hundred years ago to the day. On come the film credits, and then the movie starts - which is the story about what the curse originally promised, the revenge of the pirates. The introductory scene is dense in stereotypography. But rather than smash the cliché or undermine it, it is totally played out and fully lived. The contemporary Horror film rarely denies its clichés, but instead accepts them, often causing an undercurrent by overplaying them.

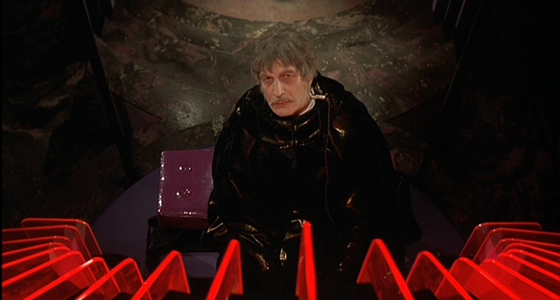

Another twist on the emphasis of the tale as a basic narrative form for the Horror film is the cinematic realization of the textual organisation of the comic book. The most famous of Horror comics were the E.C. comics from the early 1950s, the style and form of which have influenced the contemporary Horror film to a large degree. Although Hammer Horror films were mainly derived from gothic literature and imagery, the 1971 film The Abominable Doctor Phibes is perhaps the first cinematic version of an E.C. comic. Amounting to not much more than a speedy revenge tale full of truly inventive and gory deaths, The Abominable Doctor Phibes combines the macabre with the hilarious in a way that was picked up in Milton Subotsky's Amicus films Tales from the Crypt (1972), and Vault of Horror (1973) and carried on in the outlandish Paul Morrissey films Blood for Dracula and Flesh for Frankenstein (both made in 1974), culminating in George Romero's exacting homage to E.C., Creepshow (1983). Creepshow in particular is notable not only for how it puts cinematic language at the service of the comic-strip (the reverse is usually the case in nearly all comic adaptations) but also for the incredible variation in tone of each of the five stories, ranging from the farcical to the horrific. Still, it is humour that remains one of the major features of the contemporary Horror film, especially if used as an undercutting agent to counter-balance its more horrific moments. The humour is not usually well-crafted but mostly perverse and/or tasteless, so much so that often the humour might be horrific while the horror might be humorous. Furthermore, the joke or punch line is imbedded in the film text and does not function separately from the film. As such, the humour in a gory scene is the result of the contemporary Horror film's saturation of all its codes and conventions - a punch line that can only be got when one fully acknowledges this saturation as the departure point for viewing pleasure.

The film that most clearly illustrates this is The Evil Dead (1982) which is a gore movie beyond belief that has one simultaneously screaming with terror and laughter (as opposed to the jarring effect attempted in American Werewolf m London). After almost deliberately setting itself up as a boring cheap horror flick, it suddenly pulls out all the stops when a possessed girl thrusts a sharp lead pencil into the ankle of a girl and swirls it around making mince meat out of her ankle - in real time and full close-up. A similar effect is used in the now seminal (though not as funny as The Evil Dead) Friday The 13th where the girl who appears to be the main star suddenly gets her throat slit in a totally non-eventful way, causing a dull thud with its awkward and messy depiction of her death.

And I could go on - having not yet even mentioned the classical construction of Alien (the most flawless suspense text I've yet encountered); the meeting of a Disneyland sentimentality with traditional avant-garde technical experimentation in Poltergeist (1982), or the Slasher sub-genre initiated most forcibly by Halloween. But the contemporary Horror film is always changing as each new film sets new precedents and new commentaries on special effects, plot, realism, horror, suspense, humour and subject matter, which effect whatever films are to follow. 'Horrality' is thus a mode of textuality that is dictated by trends within both the Horror genre and cinematic realism. But what amounts to an awkward problematic in analysis and writing in fact works very productively in the viewing of the films, and it is at this point in film history that one is able to experience the speed of this genre about genre.

Text © Philip Brophy 1983 & 1985. Images © respective copyright holders