Picturing Musical Creativity & Emptying the Self

Picturing Musical Creativity & Emptying the Self

Terre Thaemlitz’s Soulnessless

published in Real Time No.115, Sydney, 2013Terre Thaemlitz’s Soulnessless (2013) has been largely reviewed in line with its format: a 16GB micro-SDHD data chip filled to its digital brim, qualifying as the “world’s longest album in history” and the “world’s first full-length MP3 album” (as it says on the release’s slip cover). But there’s much more happening in Soulnessless than its demonstrative act of formatting. Unlike the bulk of ‘politicised technological boutique sound/noise/digital’ releases trading in purported commentary on the means of their production, the state of nowness, and the humanist intervention of their endeavour, Soulnessless is empowered by an unerring insularity and asocial tenor which emboldens and clarifies its purpose in reflecting on what it means to produce (more than merely ‘release’) music for the listener today.

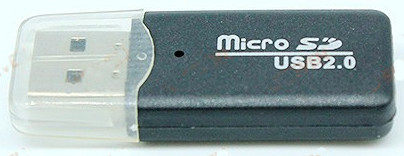

To simply describe this complex work: Soulnessless is 5 extended compositions based around piano recordings, digital processing, layered record samples, and occasional onsite interviews, all loosely but carefully addressing symbolic relationships and aural similarities between (a) the extended contemplative states endeared by Minimalist and ‘ambient’ musical composition, and (b) the ecstatic and transcendental states induced by Catholic rituals of prayer. The micro-SDHD contains 5 ‘cantos’ (the 5th being an acoustic piano improvisation recorded in a single near-30 hour take), some remixes, an MP4 video of the first 4 cantos, and assorted PDF documentation and commentary. (In the spirit of Soulnessless’s complexity, I’ll discuss in detail a few tracks, rather than attempt to précis its whole corpus.)

This perplexing density of content and form is quintessential Thaemlitz. It bears Terre’s distinctive and fascinating cross-wiring between gender politics, transsexuality, classical music’s sexual repression, gay culture’s musical hedonism, and the pop industry’s relentless promiscuity, all swirled into a treacle of viscous thought and technological queering. Viewed in light of Terre’s artistic history, Soulnessless is a pinnacle of how he has concentrated these interests and pursuits into a single work (as unwieldy in size as it is). Soulnessless’ ‘insularity’ is exemplified by Terre’s alignment of the male computer musician with the female Catholic nun, each cloistered within their mental tomb (scroll bars and sound loops in the former; temporal regimes and prayer cycles in the latter). "Canto I – Rosary Novenza for Gender Transitioning" features a group of nuns (or maybe just church-goers) reciting the Catholic rosemary. It doesn’t take much prompting to reinterpret their droning unison as a type of ‘effects plug-in’ which diffuses their sound and renders them into a post-human (or transcendental) state. After all, where would electronic music of all persuasion be without artificial simulation of Baroque church acoustic architecture and its ether-inducing reverb? Terre’s clinical ease in presenting this recording unadulterated for 3 minutes before a single piano chord rings forth enables such a contemplation. It’s a remarkable act of listening more than sound-making, reminding one of Annea Lockwood’s recordings of spaces: her works are acoustic testaments to her aural encounters. Yet unlike either eco-globalist field recording discourses or Cagean Zen-inflected welcoming of pure sound, Canto I applies modernist secular approaches to aural awareness while retaining the most over determining aspect of the sound’s cultural content, i.e. Catholic rituals. The most predictable dialectic of field recording lies in its attenuation of ‘real world’ events to imply veracity, but "Canto I" perversely applies field recording to the ‘unreal world’ events of religious practice. Most surprisingly, the result is not anti-Catholic, but strangely post-ecclesiastical. As fiery as Terre’s polemics have always been, a calm quells any melodramatic fire and brimstone critique which besets most Catholic revisionism.

The calmness of "Canto I" is no superficial emotional by-product. It’s the result of Terre’s gauging how so-called ‘ambient’ music can be considered its opposite: a disquieting realm of cultural noise and interference. Terre literally brings the noise to queasy realms sanitized by decades of Minimalist and ‘ambient’ decontextualization. The aural ectoplasm of the nun’s choral dribbling could be aligned with Gavin Bryar’s impressively clinical reprocessing of inebriated babble in Jesus Blood N’er Failed Me Yet (1975), but "Canto I" suggests less of an observational frame placed around social occurrence and more of a reflective trip inside the heads of the nuns themselves. If there is a Minimalist precedent, it would be Robert Ashley’s Automatic Writing (1979), where the listener lies at the threshold of Ashley’s somnambulistic rambling. "Canto I" sets audible voices against inaudible voices, aligning the nuns incanting while listening to the inner voice of God addressing them, with Terre the composer voicing his own voicelessness, evoking what poetically arises as a transgender purgatory. Even the fetishistic glitch processing has its place in this queasy meld of celibates and celebrants: that familiar computer clicking sounds like rosary beads clicking.

The title "Canto II – Traffic With The Devil" could evoke the dumbo macho mysticism of Sun O))) and their doomy cartoony ilk. But a careful listen (again, facilitated by the long-form nature of the Soulnessless project) evidences not an erotic wonderland of granular complexion or collapsing realms of saturated noise, but an inverse world of immaterial complexity born of a lack of ‘soul’ (i.e. ‘soulness’). The track feels like a deliberately artless computer-grid of cut-and-paste data (the X-Y verticality of digital placement simulating an act of construction). It harkens back to the future lazily dreamt of in early 90s MIDI-dependent ambient/trance/techno (before Warp and Mille Plateaux exponentially complexified those beginnings). "Canto II" not only parodies the numbing mania of cut-and-paste reflexes: it hollows out those tropes to produce a severely scaled-down automatism rendered with the texture of its immateriality. Maybe we’re hearing processed fragments of piano events from "Canto V", but neither the originating grain nor any resultant timbre are as important as the residual aura of their computerized congregation and assimilation.

The Soulnessless project stridently accepts this as a reality-effect of democratised computer production, wherein musical composition never achieved the Stockhausian utopia of ‘trans-orchestration’ or ‘techno mysticism’. In short, "Canto II" plainly demonstrates the artefacting of its own existence. Terre’s compositions are relentless acts of emptying; the Cantos are not heroic acts of faux-radicalised musicality (as if Wagnerian ideals still need to be railed against in the 21st Century) but signs of synchronism between the Self and one’s selflessness in the face of immaterial technological production. "Canto II"’s arching emptiness and contracted repetitiveness is not about Minimalism, Techno or Minimal Techno, but about how those musical genres symptomise macro conditions of how music is figured and configured in the present of our over-historicised times where everything is ruthlessly contextualised, placed and fixed.

The negative impulses felt in Soulnessless are wonderfully didactic, for they proffer ways in which one can reductively and deductively ‘picture’ musical production – via a semiological reading (parlaying religious iconography into technological praxis as in "Canto I") or a textual reading (acknowledging the empty effects of ‘computer creativity’ as in "Canto II"). The negative world of Soulnessless is a great place to visit – because it’s where you’re already living.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © Terre Thaemlitz..